Spirituality in the Secular Literature Classroom

I teach secular literature and am an Orthodox Jew. Nothing about that statement feels inherently contradictory, and in the Modern Orthodox world, those two aspects of my life fit seamlessly together. It is widely accepted in our community that we have much to learn from the secular world, and our educational system is structured to highlight the profound value we can gather from all peoples and perspectives. Modern Orthodoxy has determined ways — more and less logically complex, depending on the topic — to integrate worldly knowledge into our traditional worldview. My students seldom question the import of studying secular literature and can deftly articulate the ways that literature contributes not only to their pragmatic future success but also the ways that it shapes them as human beings and as Jews.

For me, literature is the most potentially spiritual of secular studies; it invites readers to feel and inhabit it, experiencing the world through another’s eyes. This pursuit leads necessarily to spiritual feelings, to the human connections that heighten our awareness of God’s creation. Literature asks readers to turn inward and outward simultaneously, using the experience of the other to understand the world and oneself, and thus it is deeply meditative, asking us to reflect, both individually and collectively, on our place in the world and our relationship to it, which is, itself, a spiritual discourse. This is the attitude with which I approach teaching literature in the Jewish Day School classroom, not as a subject separate from Tanakh or Gemara but as a complementary study; aspects of textual analysis, regardless of the type of text, obviously overlap but, more than that, literature enables us to feel God’s presence in our lives through the beauty of language and the miracles of human creation.

In my readings, even a deeply religious poem from a Christian poet, like Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “Pied Beauty,” speaks directly to my sense of the world as a religious Jew.

Glory be to God for dappled things –

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that

swim; Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough;

And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim.All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows

how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle,

dim; He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

Hopkins’ biography illustrates that his sense of God differs significantly from mine, but the poem itself feels — to me, at least — quite Jewish, particularly in its use of tehillim as its structural model. Indeed, the poem begins with “Hallelujah” and ends with “Baruch hu,” and in between it focuses on one specific aspect of God’s creation: the beauty and variety of multicolored (“pied”) creations, those both natural and those associated with humankind. In its listing of such items, this Victorian take on the genre of psalms resembles any number of piyyutim that list reasons to see God in the world and serves as a reminder of God’s presence in even the smallest aspects of creation. In this case, Hopkins’ own Catholicism seems utterly beside the point, and the fact that his faith grows from the Jewish tradition allows for a textual overlap — heightened by his fluency in Biblical Hebrew — that enables Jews to appreciate his poem and to interact with it as a spiritually moving text even without appreciating the entirety of his faith system.

And if we restrict our reading of secular literature to poems like “Pied Beauty,” we seldom need to confront the ways in which secular, or even Christian, literature less comfortably fit with a Jewish worldview. In fact, the kind of universalism that “Pied Beauty” enables is very simple: we are all one people, across cultures, with one God and a shared notion of the majesty and miracles of the world. As a reader, I can easily set aside Hopkins’ actual theological perspectives and replace them with my own, reading “Pied Beauty” through my lens and thereby feeling not only fully secure in my belief system but also inspired by the neat conformity of other belief systems with my own. I can unite the particular and the universal to sit comfortably with my own worldview, which is not only particularistic but deeply invested in universalism.

This approach is quite popular in Modern Orthodox circles, and we see it pointedly in Rav Aharon Lichtenstein’s widely-known analysis of Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.” Someone shares this analysis with me at least once a year, and that fact alone suggests its import and the comfort it offers Jews who want reassurance that secular literature integrates seamlessly with Orthodox belief and practice. That a great rabbi whose erudition is broadly admired in Orthodox circles finds value in secular literature, going so far as to earn a PhD in the subject, feels like the validation we need in order to continue striking the subtle balance required by Modern Orthodoxy.

R’ Lichenstein, in his unique analysis of this poem, writes that the narrator “pauses amidst the excitement of his life. His ‘stopping by woods’ reflects the extraordinary magic this natural scene exerts upon his imagination. It is a moment of wonderment. There is something in the woods’ beauty that draws him in, lures him, encouraging him to abandon his anxious self-consciousness.” R’ Lichtenstein goes on to explore the narrator’s apparent bifurcation and Frost’s as well, noting that both of them must choose between two worlds, the “lovely” and the “dark,” to use Frost’s language from the poem, which R’ Lichtenstein interprets as the “aesthetic” and the “ethical.” This is a beautiful, moving reading that examines the bifurcated experience of observant Jews in the modern world and that highlights the spirituality Jewish readers can feel even when exploring a poem like this one, written by a Christian author.

R’ Lichtenstein chooses to explore a poem that is implicitly rather than explicitly Christian — as so much Western literature is — but feels, on its surface, fully secular. R’ Lichtenstein does nod to the poem’s Christian iconography in noting that “Christian tradition identifies the apple as the ‘fruit’ eaten by Adam and Eve. That story represents the origin of all moral obligations, the ‘knowledge of good and evil’; the apple is a symbol laden with meaning.” But even that narrative is shared by Jews and Christians despite our disparate interpretations of its import. In a footnote, the rabbi offers insights into Frost’s personal ambiguity regarding faith, observing that “Frost had a certain religious bent, and it is therefore possible to explain this poem as a spiritual analogy. The wood’s absent owner is God ‘hiding His face’; morality and aestheticism can be seen as two alternative spiritual paths.” This footnote aims to elucidate Frost’s own spiritual feelings, but those are not central to the essay’s primary argument. In his essay itself, R’ Lichtenstein elects a Jewish particularist view, although he does not name it as such, relying on a Jewish perspective to read this secular or, possibly, Christian-leaning poem as a lesson about Torah: “I know of few poems that express so forcefully the moral idea that binds us to the beit midrash... One who sees the beauty in God’s creation, who comes to love it, must be strong in order to devote himself to learning Torah.”1 This amazing bit of literary analysis posits that this poem is, in fact, about Torah. His footnote acknowledges the more common biographically-shaped meaning, but the body of his analysis argues that this poem, written by a poet who never set foot in a beit midrash and likely never even heard of one, unproblematically reinforces an explicitly Jewish view of the world.

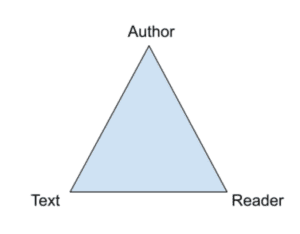

In this reading, Frost’s views and intentions are unimportant, and the reader’s perspective shapes the poem’s “true” meaning. In other words, I can read “Stopping by Woods” as a Jewish poem because I am Jewish and everything, for me, is Torah. This approach runs counter to more conventional literary interpretive methodologies that maintain a set of “correct” analyses, most of which rely upon conventional biographical or critical close readings and ask readers deliberately to omit their own beliefs or feelings from their interpretive process. Approaching texts, as R’ Lichtenstein does, not searching for authorial meaning but for personal, readerly meaning, raises important questions not only for the reading of poetry but for the teaching of poetry. Can every poem, however outside our tradition in its composition, be a poem about Torah so long as its reader is a Torah-loving Jew?

The logical extension of this approach is that, in all of our text study, biographical meaning — the question of what the author intended — should not take precedence over affective meaning; the reader’s feelings and experiences have as much, or even more, credence in understanding a text than the author’s feelings and experiences do. Avoiding affective readings entirely — while sometimes a stated goal of literary analysis — is fundamentally impossible, and so R’ Lichtenstein’s piece feels, to me, like an acknowledgment of something we do regardless of whether we admit it. We may prefer to believe that we are capable of removing ourselves from the reading process and reaching a “pure” understanding of an author’s perspective. And, of course, the very nature of English class, including the presence of grades, which imply better and worse interpretations if not fully “right” and “wrong” ones, works at cross purposes to an interpretational strategy like R’ Lichtenstein’s. No “objective” reading of Frost’s poem could argue for the presence of a beit midrash therein. And yet R’ Lichtenstein clearly feels a deep truth in his reading of the poem, and his interpretation’s prominence highlights its resonance for other Orthodox readers as well.

His approach underscores that a triad of potential meanings exists, and all of them remain part of every reading experience: the author, the text itself, and the reader.  Any reading experience may rest at any point in the triad. I might aim to privilege an author’s view, for example, and therefore use his biography, letters, diaries, and other works to interpret a text. Or I might aim to learn as little as possible about the author, privileging the text above all as an independent entity that exists out of time and place. I might, as R’ Lichtenstein does in his interpretation of “Stopping By Woods,” privilege the reader’s view, extracting meaning from the poem through the lens of my own beliefs and experiences. Many interpretations fall somewhere along the triad’s external lines or in its middle. Various literary theories over the years have promoted each of these interpretive positions, and all of them have a place. To some degree, though, even when we aim to eliminate one part of the triad and focus wholly on another — such as E.D. Hirsch’s argument that the reader’s goal is exclusively to understand the author’s intended perspective, ignoring one’s own experience and anything the author might have said unintentionally — we cannot completely ignore the triad; all three aspects exist, to greater or lesser degrees, in every reading experience. We cannot be anyone but ourselves, even as we endeavor to step away from ourselves for some time as we are immersed in a text.

Any reading experience may rest at any point in the triad. I might aim to privilege an author’s view, for example, and therefore use his biography, letters, diaries, and other works to interpret a text. Or I might aim to learn as little as possible about the author, privileging the text above all as an independent entity that exists out of time and place. I might, as R’ Lichtenstein does in his interpretation of “Stopping By Woods,” privilege the reader’s view, extracting meaning from the poem through the lens of my own beliefs and experiences. Many interpretations fall somewhere along the triad’s external lines or in its middle. Various literary theories over the years have promoted each of these interpretive positions, and all of them have a place. To some degree, though, even when we aim to eliminate one part of the triad and focus wholly on another — such as E.D. Hirsch’s argument that the reader’s goal is exclusively to understand the author’s intended perspective, ignoring one’s own experience and anything the author might have said unintentionally — we cannot completely ignore the triad; all three aspects exist, to greater or lesser degrees, in every reading experience. We cannot be anyone but ourselves, even as we endeavor to step away from ourselves for some time as we are immersed in a text.

Once teachers admit that fully omitting one’s own beliefs from the reading process is an impossibility, we must accommodate students’ own experiences and affective responses, which means enabling and encouraging students to find spiritual resonance in non-Jewish texts, as R’ Lichtenstein does. If they can see the beit midrash in Frost’s work, we shouldn’t tell them they are wrong. Of course, when we exclusively privilege authorial intention, then they are wrong by that limited standard, but when we consider reader-response a legitimate site of meaning, then they are right. When we move in this direction, however, we might also choose to move towards assigning texts to which we feel students can more naturally relate, which has increasingly occurred in English curricula in recent decades even as we work to diversify writerly voices. Doing so might mean increasing the percentage of Jewish writers we include in our curricula, especially if part of our aim is to bring spirituality into the English classroom. But can we enact Rav Lichtenstein’s principle that everything, even Robert Frost’s work, is Torah and apply it to poems that are less externally secular than “Stopping by Woods”? That sort of curricular choice requires a universalizing of belief that may not appeal to audiences in particularist Jewish settings. And it may awaken latent New Critical tendencies as we worry that we are teaching these texts “the wrong way,” prompting students to reach “incorrect” or otherwise worrying conclusions through their individualized interpretations.

A second Gerard Manley Hopkins poem can help us illustrate this point:

The world is charged with the grandeur of

God. It will flame out, like shining from

shook foil; It gathers to a greatness, like

the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his

rod? Generations have trod, have trod, have

trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man’s smudge and shares man’s smell: the

soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs

—Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

This poem, until its end, also speaks to a universal religious experience in its generalized appreciation for God’s creations as well as for the renewal of each day. Hopkins draws readers’ attention to the ways people have ignored or blighted God’s creations and separated themselves from the natural world, but at the sonnet’s volta — the pause that separates its two unequal halves — he offers readers a “yet” that reinforces God’s divinity and His miracles: despite “all this” degradation of nature, nature continues to return: “deep down things” regenerate, and the sun rises again each morning. Hopkins closes this poem of deep appreciation for nature with a particularistic Christian image: the Holy Ghost, often envisaged as a bird, leaning over the earth as a protective mother, with the earth, its egg, sheltered under its wing.

Without the Christian resonance that the “Holy Ghost” image provides, this poem, too, feels profoundly applicable to a Jewish context if we privilege readerly meaning. It is a poem of hope and gratitude, highlighting human responsibility for environmental destruction and our ability to partner with God to repair the damage we have done, thus allowing us, once again, to feel the earth beneath our feet. The image of the Holy Ghost conjures a metaphorical vision of God similar to the “strong hand and outstretched arm” of the Exodus story or the “countenance” of the priestly blessing. It is not, for me, a necessary acknowledgment of the trinity, as it certainly was for Hopkins. And yet his use of “Holy Ghost” language, coupled with my knowledge of his authorial intentions in choosing it, requires a clear distinction between the meaning of the poem as its author intended it and the meaning of the poem as its reader (me, in this case, or perhaps my students) receives it.

Universalizing this poem in the Jewish Day School classroom can render an “accurate” reading of the text only if we are comfortable with a reader’s perspective holding equal accuracy as an author’s. In this case, students need not see distance from their own beliefs in the final couplet nor necessarily adjust their reading to accommodate Hopkins’ deep Christianity. For the most part, my experience in the classroom has shown that students either absorb that final image into their own worldviews and are not troubled by the bird-like Holy Ghost, which means nothing to them in any case, or ignore it altogether, focusing instead on the poem’s imagery that fits more readily with a Jewish approach: the ooze of oil, the trodden earth, the miracle of sunrise, and the implicit judgment rendered against those who do not appreciate God as we (Orthodox Jews and Hopkins) do. Thus, through the lens of Jewish readers, the poem becomes — as Frost’s does for Rav Lichtenstein — a powerful expression of Jewish faith, a spiritual reading experience for Jewish students, Hopkins’ own contrary beliefs notwithstanding.

Even a poem like “God’s Grandeur,” therefore, can relatively easily be integrated into the Jewish Day School classroom, providing a universal reassurance of the shared experience of people of faith, an opportunity to use the English class as a site for spiritual growth without tension or conflict. But this attempt at integrating secular literature into the Jewish classroom can be taken further still, moving us even farther from the easy integration of secular literature into Jewish spirituality. Here is Hopkins’ poem “As Kingfishers Catch Fire:”

As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw

flame; As tumbled over rim in roundy wells

Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung

bell’s Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its

name; Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves — goes itself; myself it speaks and

spells, Crying Whát I dó is me: for that I came.I say móre: the just man justices;

Keeps grace: thát keeps all his goings graces;

Acts in God’s eye what in God’s eye he is —

Chríst — for Christ plays in ten thousand

places, Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not

his

To the Father through the features of men’s faces.

This poem, similarly beautiful and filled with the same religious fervor and appreciation of God’s work in the world as “Pied Beauty” and “God’s Grandeur,” is harder to adapt to my Jewish worldview. Its multiple explicit mentions of Jesus naturally separate me from the work, and I have to labor more — and with more apologetics — to find my own religious resonance in this poem. While I feel, indeed, that each mortal thing has its God-given purpose and that “the just man justices,” a play on words whose profundity grows with greater reflection on the phrase, the upshot of the poem — that each of us contains or is some portion of Christ — does not speak to me at all. I can replace “Christ” in the poem with “God,” just as I replaced the Holy Ghost in “God’s Grandeur” with God, but doing so in this poem, with its extended and deeply particularistic references to “Christ,” a religious image to which I have a deeper, more visceral resistance, provides a less spiritual experience for me even though, in many ways, it is the most powerful poem of the three.

As a teacher, my gut reaction is to teach the first two of these Hopkins poems and simply omit the third from my classes. Doing so permits me to avoid my own discomfort with “Christ’s lovely limbs” and sit easily in the center of a Venn diagram that encompasses both my Jewish and literary values. But that kind of pick-and-choose curriculum development — like pick-and-choose Judaism — isn’t sufficiently honest. It does not allow me, and more importantly does not allow my students, to make the complicated intellectual choices necessary to achieve the deepest, most meaningful insights. It should come as no surprise that spirituality requires some level of discomfort, and we are fairly accustomed to approaching that discomfort in terms of various apparent inconsistencies within Jewish texts, such as the injunction to love our neighbors juxtaposed with the ways in which we are simultaneously told to treat them with something less than love; difficult questions lacking fully rational answers, like theodicy; or potentially ethically problematic statements, such as those regarding Amalek.

Those are issues we must raise because they are inherent in our texts. To ignore them would feel explicitly disingenuous. But issues of religions outside of Judaism need not be raised in a Jewish context, and so we tend, instead, to ignore them or study them through a sociological or historical lens, which feels more safely distant from our own spirituality. This hesitation grows from understandable and long-standing fears about too much exposure to the other. Even in a very modern environment, the idea of exposing students to explicit statements of faith other than those of Judaism feels not merely inappropriate but potentially dangerous. And yet the experience of studying another’s faith can be a powerful and spiritually enlightening experience if we can overcome the natural fear that accompanies such study, especially for Jews studying Christian works, with the long and painful history of proselytism and oppression that is inevitably raised by such encounters.

Perhaps more importantly, studying such poems is true. In other words, these overtly religious poems exist, and they exist for reasons of poets’ belief in a God who is not purely universal despite some historical and theological overlap in our conceptions of God. Omitting uncomfortably particularistic texts from our literature classrooms may, in fact, be more “dangerous” than including them because consistent universalizing elides religious difference. When we perform the work that R’ Lichtenstein models for us, we may unintentionally create for students a sense that Christianity is foundationally identical to Judaism. When we can find Torah in everything we read — and we only read texts in which we can find Torah — we ignore elemental distinctions among people and groups that should be essential to students’ educations.

One purpose of the study of literature is to understand another’s perspective. English teachers constantly aim, with every text we choose, to expand students beyond themselves, to offer them the opportunity to see a different life or culture or world. Literature’s greatest gift is its ability to enlarge our vision, giving us insight into the other. What we generally do with this gift, though, is turn it back to ourselves: how do you “relate” to this text? What messages can you find in it for your own life? That broadening followed by a narrowing has real value and can enable students not only to look beyond themselves but also to apply their new views to their own lives. But we may focus too much on the narrowing and not sufficiently on the broadening as we aim to comfortably situate students in two worlds.

However, when we study deeply religious works of other faiths, those that can not easily be universalized, we are comfortable broadening our views and discomfited when the narrowing begins. Rather than ignoring these texts, though, we can argue that relatability need not be the goal. And students already understand this principle because they regularly confront texts that feel inapplicable to them or that, in their parlance, they “can’t relate to.” But if, instead of seeing this unrelatability as a failure, we explain that certain texts broaden out to others and then narrow back to us while other texts broaden out to others and remain there, broad and, at least partially, inapplicable in our own lives, we open for students a larger world of texts and ways of reading.

Distancing — or broadening without narrowing again — is often harder than reading more evidently relatable texts, and therefore it can be less pleasant. When a text is not “about” me, I may have less interest in reading it. But, in fact, English teachers often try to find texts that are just outside students’ purviews to create that natural balance between “it’s all about me” and “it’s not about me at all.” When we bring spirituality into this conversation, we must differentiate feeling spiritual as the poet or speaker does (as in “Pied Beauty”) and feeling the power of someone else’s spiritual feelings that we ourselves do not share (as in “As Kingfishers Catch Fire”). I can find aesthetic beauty in medieval European art or Methodist hymns without being religiously moved by them, and aesthetic appreciation may prompt a kind of spiritual feeling.

The power of seeing oneself in a work of literature is self-evident. The power of seeing someone utterly unlike oneself might require more explanation, but it too has deep value. If students believe that every person is fully relatable through our literary selections because we are all fundamentally the same, they may profoundly misunderstand the nature of the world. People are the same in certain ways but not in every way, and religions — especially monotheistic religions — have significant overlap but are far from identical. While English teachers might understandably choose more naturally relatable texts because students tend to like them more, we miss an educational opportunity if we elide difference or teach only texts in which students can see themselves.

When I teach John Donne, among the most deeply religious of English poets and a remarkable, truly astonishing craftsman of language, I begin with “Death Be Not Proud,” a largely universal poem about how we convince ourselves not to fear death.

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;

For those whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be,

Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee do go,

Rest of their bones, and soul’s delivery.

Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate

men, And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell,

And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well

And better than thy stroke; why swell’st thou then?

One short sleep past, we wake eternally

And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.

Students note the various ways, in Donne’s sonnet-form list, that he convinces himself that death lacks power. They sense his deep religious faith and his trust in God’s goodness and in an afterlife, an olam haba, to which souls awake. They likely fear death themselves and may find religious resonance in his arguments, and they may feel momentarily convinced that Donne’s speaker believes his own arguments. But inevitably, even among freshmen, some students notice that Donne protests too much, that his bold exclamations may serve as a cover for his fear. That deep relatability — the coexistence of faith and worry, of the “right” words juxtaposed with the “wrong” feelings — speaks powerfully to students’ own religious struggles. Donne’s religious faith merges easily with ours, and the complexity of his emotions mirrors many of our own momentary or long-lasting emotional and theological tensions. After such a productive and personal discussion, I may feel satisfied that I’ve taught Christian poetry comfortably in the Jewish classroom.

But there’s so much more. In fact, I feel duty-bound to then show students this poem from the same sonnet sequence:

Batter my heart, three-person’d God, for you

As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to

mend; That I may rise and stand, o’erthrow me,

and bend Your force to break, blow, burn, and

make me new. I, like an usurp’d town to another

due,

Labor to admit you, but oh, to no end;

Reason, your viceroy in me, me should

defend, But is captiv’d, and proves weak or

untrue.

Yet dearly I love you, and would be lov’d fain,

But am betroth’d unto your enemy;

Divorce me, untie or break that knot again,

Take me to you, imprison me, for I,

Except you enthrall me, never shall be free,

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

Break me? Imprison me? Ravish me? The poem asks God to destroy the speaker through brutal violence and even rape, and remake him from new in order to eliminate the sin in him. This language feels completely foreign to my understanding of God, and indeed it is. Of course, I can find some Jewish historical notions of God’s punishment of the body as a means to reach Him, perhaps in echoes of the martyrologies that we recite on Yom Kippur and Tisha B’Av or in the isolated medieval Hasidei Ashkenaz movement or the European Novardok Yeshiva, which held an ascetic philosophy. But these are not typical Jewish ways of thinking about our relationship with God, as contemptus mundi (moral disdain for physical existence) is in Christian philosophy. And in the extreme situations of the martyrologies, the savaging of the body is performed by Jews’ tormentors, not by God Himself. We never hope or pray, as Donne does, for ourselves to be the recipients of that brutality; we recognize it as an historical event that has occurred because people hate us, a fact for which we mourn.

Perhaps even more noticeably, the opening image of a “three-person’d God” cannot be dismissed as an unimportant theological difference that we can overlook to find universal appeal. In this case, Donne is genuinely speaking to a god who is not my God, not only because his prayer is so different from mine but because the god to whom he prays is not mine. I have no conception of a three-person’d god any more than I could think of Vishnu or Ganesh as a deity. But I can see how much this image means to Donne and to his speaker, and I can hear what he’s saying by broadening my vision even if I cannot apply it to my own life by narrowing it again.

What we see in “Batter My Heart” is an alien theology, one that envisions the body as betraying the soul and that needs God to intervene and cause bodily harm in the service of soulful renewal. Naturally, this wish has its roots in the crucifixion, where bodily torture leads to eternal salvation, and so Donne’s speaker asks for a lesser version of this same transformation. There are countless ways in which this poem does not speak to Jews, and shouldn’t. We elevate the body rather than degrade it, and we value bodily pleasure — in the right ways, and at the right times — above asceticism. We have no tradition of self-flagellation nor of a god who physically suffered in order to free our souls. While we are not hedonists, we do not see the body as a betrayal of our truer inner selves, and instead we aim for a unified sense of body and spirit, a holiness of each and of both together.

However, I can hold my own views and also hear Donne’s, and in order to be truly educated about the world, I need to be capable of doing both. I need to know that when Donne writes in “Hymn to God, My God, in My Sickness,” “Look, Lord, and find both Adams met in me,” he is not, as my students inevitably assume, writing about Adam I and Adam II of Lonely Man of Faith. He is referring to the Adam of Genesis and to Jesus, the “second Adam” of Christian typology: “As the first Adam’s sweat surrounds my face,/ May the last Adam’s blood my soul embrace.” Knowing that fact changes the way I read the poem and also the way I see the world; it changes my understanding of the Christian other and helps me to see him not through my own lens but through his. Of course, I cannot fully observe the world through any lens other than my own because I cannot leave myself entirely, as the triad above illustrates in its interconnectedness. But part of the goal of literature is to leave myself to the extent I am able and to learn about a view that is not mine. I cannot be a full citizen of the world — or even a fully spiritual being — without forcing myself to look through a range of lenses. “Death Be Not Proud” shows me a new perspective through a lens I already employ; “Batter My Heart” replaces the lens with a different one altogether. Literature should enable me to do both and to empower me to choose which lens I use in any given reading experience.

I can also make a conscious choice, as R’ Lichtenstein does in his Frost analysis, to step back from Donne’s intentions and read the two Adams as Adam I and Adam II. I can explore what this poem means to me using Donne’s language in a way that could never have occurred to Donne himself. I can place Donne in the beit midrash and see what happens to him when he’s there. That is a legitimate interpretive choice, but it is not the only one. I can use the triad of interpretation to see where I exist in my analysis and where Donne does, and I can choose the interpretation that works for me in any particular moment. But I — and my students — should know how to look through multiple lenses, the Jewish one that is most natural to us and the Christian one that is most natural to the poet and his speaker.

I needn’t be afraid to look through the Christian lens nor teach it to my students because it will almost certainly never become mine, nor theirs. And our fear in the Orthodox community is generally not that our students will convert to pious Christianity as it may have been in the Middle Ages or during the Inquisition. Instead, we fear that our students will become fully secularized, finding the appeal of generic “American” life — which includes a kind of neutralized Christianity — a smoother ride than the life of halakhic observance that we have to offer. Donne and Hopkins likely feared the same for their students, worrying that a less devout Christianity was both more appealing for the general population in daily life and more treacherous for the long-term prospects of the eternal soul. The power of their faith reverberates in me and creates a certain aspect of relatability that their faith itself does not. But pretending that their faith and mine are the same — that only “Pied Beauty” and “Death Be Not Proud” exist and that “As Kingfishers Catch Fire” and “Batter My Heart” were never even written — universalizes our experiences to such an extent that I may end up, inadvertently, making neutral Christianity seem more appealing in its familiarity and closeness rather than less so. If, in my discomfort with particularistic Christian texts, I avoid them in the Jewish day school classroom entirely, I may unintentionally suggest to students that our traditions are identical, easily integrated into one another.

To be clear, the primary reasons for teaching the full range of texts, including those that feel uncomfortably Christian, is that they offer greater truth into the experiences of a wider range of human beings and because we are, as educated people, responsible for knowing as much as we can rather than as much as is comfortable. But the fact that too much universalizing can also be problematic in the ease with which it presents belief transference might remain in the back of our minds.

Showing students the foreign as well as the familiar enables them to broaden themselves but also to recognize that the “Judeo-Christian tradition” discussed so blithely by scholars is actually just Christianity. Judaism is its full, own, separate entity that cannot be so easily combined with the Christianity of Hopkins or Donne. There are moments when we all seem to be engaged in the same holy endeavor and moments when the falsity of that happy, universalist narrative must become clear. Students are entitled to read and discuss both, and they can feel spiritually moved by some texts from outside our tradition and alienated by others. We can, together, explore why that is the case and what it means for observant Jews as a religious minority that aims to straddle multiple worlds. We are responsible for facing both the universal and the particular head-on — not only for ourselves but also in our classrooms — thus teaching students how to read and appreciate both relatable and utterly unrelatable texts: those firmly lodged in the beit midrash, those that can be placed there with care in the spirit of intellectual inquiry, and those that can’t even get through its doors.