On Differential Prayer

I. Institutional Goals and Student Needs

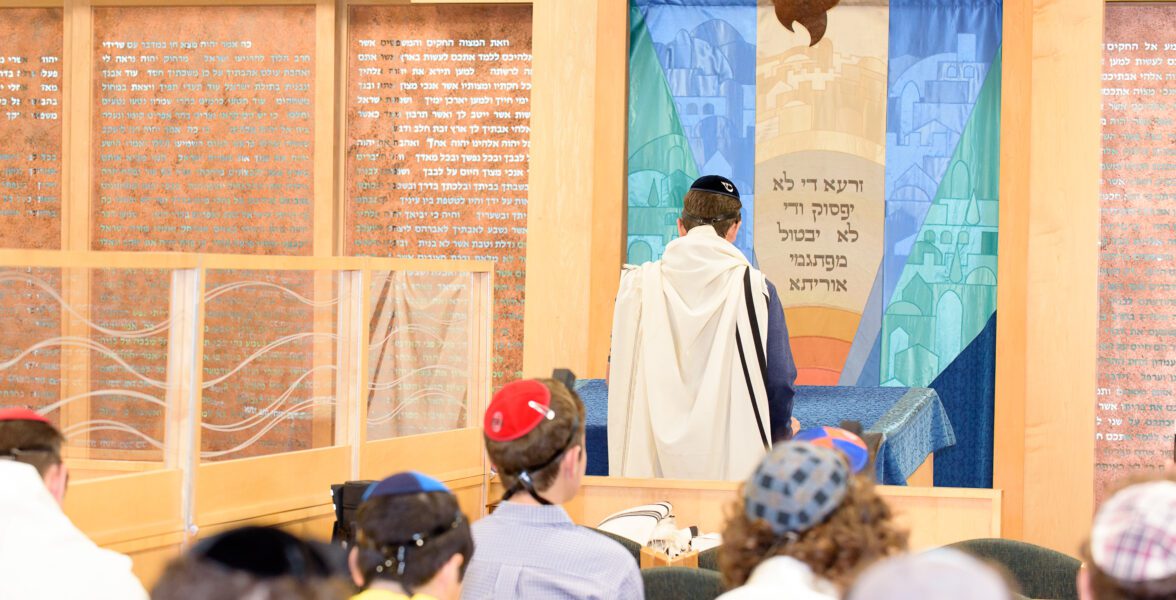

Prayer is central to the Yeshiva day school program. Since the inception of the day school model, yeshivot have begun each day with tefila. In doing so, we express our collective commitment to the importance of prayer in Jewish life. Tefila is time set aside each day, hopefully both in and out of school, for one’s spiritual connection and growth.

Carefully considered, however, our daily tefila in school achieves both more and less than we might think. In our day school system, we use the daily tefila slot to accomplish a variety of goals simultaneously without precisely articulating to ourselves or to our students what those goals are and how we seek to accomplish them. I suggest that this is one of the reasons that tefila is notoriously fraught for teachers and challenging for so many students. This is the case regarding the goals that we have for our students as well as the wide range of students’ own goals and needs.

Students are in very different places in appreciating and connecting to tefila. Some students have a natural affinity for “what is beyond,” something that the eye cannot see; for others, that concept is foreign or uncomfortable. Some students understand most or at least some of the words that they are saying; others do not understand the words but are not troubled by their lack of comprehension; for still others, lack of comprehension is a source of frustration. Some students struggle with reading. Some students like to sing; others don’t. Some students often daven with a minyan; others are not sure of what is happening at the front of the room although they would be happy to recite tefilot on their own. In day school tefila, time is short, classes are large, and the goals and needs of students are varied.

Considered broadly, prayer includes both spiritual and social goals. One aspect is more personal and the other communal. One is internal and the other interpersonal. And the skill sets are distinct as well. While difficult to articulate, the spiritual skill requires that we rupture the routines of daily life and the elements of our common experience to encounter something that is beyond, something bigger than the taking-care-of-things aspect of life, to connect to God. Developing strong spiritual capacity provides an orientation through which to perceive the world. Socialization into the shul environment informs our lives in important ways. Shul attendance shapes our community and our friendships which, in turn, shape the religious decisions that we make in our lives. If we are comfortable using the siddur, finding the right page, and understanding the ritualized practices occurring around us in shul, we will more likely find a home there and more comfortably enter the space. Once through the door, social forces propel our social and religious life in a particular direction. If we are comfortable going to shul, we will more likely live closer to the shul. In our communities, being a shul-goer shapes a person’s social life on Shabbat and during the week, the school one chooses for their kids, and the likelihood of hearing a shiur or learning Torah. If we feel like outsiders in shul, we are less likely to attend. And many opportunities are missed.

From the administrative perspective we have narrowed our focus for tefila to two broad goals: 1) helping our kids grow as spiritual and prayerful people who can experience God’s presence in their lives and 2) socializing our students into the rituals practices and patterns of davening with a minyan in shul. While these two goals overlap in many ways each is distinct. We of course hope that the morning minyan experience provides an opportunity to grow in both of these areas – spiritually and socially. But accomplishing both at once proves difficult especially in light of the range of students’ needs. Furthermore while we are trying – and should be trying – to teach both of these goals they are sometimes at odds with each other. To be properly socialized into our patterns of tefila we should recite all of פסוקי דזמרה always say חזרת הש״ץ and recite the long תחנון on Mondays and Thursdays. To develop our spiritual selves we would do better to follow the guidance of the שולחן ערוך which says טוב לומר מעט בכוונה מלומר הרבה בלי כוונה.

In order to create a plan to respond to the range of needs of our students as well as to teach towards both spiritual and social goals, we must thoughtfully articulate those needs and goals and clarify the differences between them. While, in common usage, spirituality is a self-evident goal for our students, I will argue that, while certainly important, spirituality is educationally complex and not adequate on its own. I also argue that the formal and social aspects of prayer deserve conscious and deliberate educational planning.

2. Institutionalized Models of Prayer

We often forget that young men and women are quite similar to adult men and women. We accept as a matter of course that adults relate to tefila in distinct ways and differ in the types of tefila that most move them. On a typical Shabbat in many of the shuls in which our families daven, one can find a “main minyan” with the standard formalities of our services, a Carlebach minyan and a hashkama minyan. People choose to attend the minyan that most suits their emotional needs and spiritual mindset. Some arrive on time and others come late and struggle to sit in shul. Students are no different. We recognize the validity of these differences for ourselves as adults but, too often, do not consider those factors when planning for tefila at school. And the distinctions are not new. Over the course of Jewish history, Jews have understood prayer in many different ways. I will set out a template of models of prayer to help us consider the range of understandings of prayer and how they map onto the differences between our students. 1 The following section draws on an essay by Shalom Rosenberg

תפילה והגות יהודית – כיוונים ובעיות בתוך התפילה היהודית – המשך וחידוש רמת גן

I will elaborate four models of prayer, all firmly rooted in Jewish practice in order to more clearly articulate potential paths of connection for our students. The five models are: theurgic prayer, mystical prayer, philosophical prayer, and dialogic prayer. While the text of tefila can be the same for each of these models, each brings with it a different set of goals and demands a different consciousness and mindset of the pray-er. For our purposes, these categories will be broadly defined and could certainly be further subdivided. Through articulating these broad categories, we can begin to consider the varied mindsets, orientations and mental capacities upon which different forms of tefila draw. The models overlap significantly, and I do not intend to draw sharp and precise distinctions. Rather, I hope to shed light on how people with different orientations can engage prayer in varied ways through shared practice.

Theurgic prayer might be the oldest of these models. In theurgic prayer one attempts to influence God through petitionary recitation. Prayer’s power is its ability to impact the course of events by appealing directly to God. There are intuitive similarities between theurgic prayer and magic but they are different in decisive ways. Magic is understood as an automated manipulation of the forces of nature. Prayer is a request of God to manipulate the forces of nature and prayer requires a divine decision – it is our hope that God responds favorably to our request. Biblical prayer the and many kabbalistic texts can be understood read in this way. Some בקשה section of the עמידה kabbalistic theurgic understandings of tefila are more systematic and automated; the tefilot of human beings the words that we utter keep the forces of God’s universe functioning as they should. In all of these approaches tefilla seeks to have impact beyond our this-worldly experience.

Mystical prayer is also rooted in Kabbalah but it differs in intention from theurgic prayer. The goal of mystical prayer is to cleave to God דביקות. This is an ecstatic goal as the prayer seeks to step out of the here and now in order to experience the divine. R. Isaac the Blind explains:

עיקר עבודת המשכילים וחושבי שמו ׳ובו תדבקין׳ וזה כלל גדול שבתורה לתפילה ולברכות להסכים מחשבתו באמונתו כאילו דבקה למעלה.

The central work of the thinkers and those who consider His Name, is “to Him shall you cleave”; and this is the great rule of the Torah for prayers and blessings that his thought should coincide with his faith as though he were cleaving to that which is above.”2פירוש שיר השירים לרבינו עזרא ח See

Much of Hasidic literature and many kabbalistic texts support this understanding of tefila. It is found in the writings of R. Hayyim of Volozhin and his students as well (as is the theurgic prayer described above). Of the five models described, this is the model most closely connected to what we mean when we commonly speak of spirituality.

Both theurgic and mystical prayer are oriented ecstatically; they seek to connect with that which is beyond present time space and consciousness. They might call upon the imagination in order to cultivate the capacity for that type of prayer. Alternatively one can view the work of prayer as this-worldly as a didactic experience an ongoing attempt to take stock and self evaluate. Famously R.S.R. Hirsch explained that the root of the word תפילה is פלל meaning ‘to judge’. In its reflexive form to be מתפלל is to “judge oneself” or self reflect. Through philosophical prayer, a person trains oneself to experience gratitude, to offer praise, to see the beauty of God’s world and develop an awareness of infinitude. It is not philosophical in its desire to answer large questions of existence. Rather, its goal is similar to that of classical philosophers, focused on character development, one’s ethos and the cultivation of dispositions. Philosophical prayer does not demand that the individual extend beyond her current consciousness; its goal is precisely to sharpen the sacred experience and the values that one brings to the dailiness of experience in the here and now. Philosophical prayer draws more on the rational, ethical, moral side of one’s mind and less on the imagination. As pray-ers ourselves, and as teachers of prayer, we should begin to consider how different models of prayer engender diverse modes of consciousness, call upon varied mental capacities and cultivate different awarenesses.

Dialogic prayer prioritizes direct communication with God. Davening is the daily opportunity to converse with God. R. Isaac Arama notes the difference between the recitation of the Shema where the reciter must hear his own voice with prayer of the Amida where one who recites aloud is considered of little faith (אמנה קטני). The reason he explains is that prayer is not a recitation but a conversation with God. For Rav Joseph B. Soloveitchik prophecy is God speaking with the human being while prayer is the human being speaking with God. That is the essence of prayer.

The anthropologist T. M. Luhrmann has explored the work of members of the Evangelical Christian community in practicing engaging God in actual conversation on a regular basis. She describes the rigor and regularity of developing the capacity of speaking with God.3T.M. Luhrmann, When God Talks Back. New York, Vintage Books, 2012. This takes practice and, here too, deliberate imaginative work. Luhrmann describes people of faith who “have coffee” with God every day.4https://cct.biola.edu/pray-in-this-way-tanya-luhrmann-on-the-sociology-of-prayer, accessed February 6, 2022. That includes setting the table, pouring the cups and sitting down to talk. While that might sound strange to our Jewish ears, we are striving for something similar in standing and taking three steps forward to enter into God’s presence and taking three steps back when we exit. Taking this analogy seriously, we should work on ourselves and with our students to develop the physical behaviors and actions of tefila as serious spiritual practices with an actual goal of cultivating an inner sense of entering into dialogue with Hashem.

Each individual can pray using any of these models. The same person might be inclined towards different types of prayer on different days or at various times during one’s life. But while we pray as individuals, Jewish prayer is communal prayer, institutionalized prayer. This idea informs both the fixedness of the liturgy and content of our prayer. Through institutional prayer we express our commitment to the collective to the צבור. We pray as a community and on behalf of the community. Through our actions we publicly express our commitment in the presence of others. In this sense ritual performance is an act of communication. Yet even when we pray alone we express a commitment to our own self and the community through our ritualized behavior. The performative power of ritual is expressed by the Ramban in explaining why a large number of mitzvot focus on the redemption of the Jewish people freed from slavery in Egypt. Behind many of the mitzvot is the idea of זכר ליציאת מצרים. Ramban believes that the pervasive and repetitive nature of this idea allowed it to penetrate our collective soul and shape the Jewish mindset. The public declaration of this idea creates shared commitment and belief.

וכוונת רוממות הקול בתפלות וכוונת בתי הכנסיות וזכות תפלת הרבים זהו שיהיה לבני אדם.

מקום יתקבצו ויודו לאל שבראם והמציאם ויפרסמו זה ויאמרו לפניו בריותיך אנחנו.The intention of raising one’s voice in prayers and the intention of houses of prayer and the merit of communal prayer is so that people will have a place to gather and express gratitude to the God Who created them and brought them into existence. And they should publicize that and declare before Him, “We are Your creations.”

Through communal prayer, we express our beliefs and commitments, and are witness to others’ expression of those beliefs and commitment. In doing so, we create a shared language and shared values.

3. Limits of Spirituality

I have davened in school settings for many years. Across the varied settings and ages, I find that the largest number of students are most engaged in the parts of tefila that are communal and formally ritualized. The overwhelming majority of students recite Sh’ma when we recite it together in unison. Almost all students stand for the Amidah, put their feet together for kedusha and raise יהא שמיה רבה their heels at the appropriate times. They will stand for kaddish and respond to although they might not recite ברכות השחר or פסוקי דזמרה. These are examples of the power of embodied ritual performance. In the current climate too often spirituality is considered authentic while formal ritual is considered cold and inauthentic. In the next sections I argue that it is vital to invest in training our students to find meaning in embodied practices. Meaningful ritual performance can provide individualized experience through stable and shared practice in a very unique way. To proceed along this path we need to undo the spiritual-ritual binary that has taken root in the minds of many.

For the past two years, I have participated in a research group with colleagues focused on the topic of spirituality. While studying spirituality, I considered the relationship between spirituality and tefila. In my experience, it is common today to associate spirituality with tefila, to the point that a spiritual tefila is the highest manifestation of meaningful prayer. While I recognize the power of spiritual prayer, I am concerned that establishing spirituality as the highest realization of proper tefila 1) limits the possible paths of success for our students, 2) sidelines other important religious goals, and 3) unintentionally gives credence to a growing anti-institutional sentiment to traditional, formal religious practice.

How might “spirituality talk” limit the possible paths of success for our students? Judaism’s different models of prayer (described above) reflect different understandings of Judaism appeal to different types of Jews and draw on different mental capacities. They allow for varied modes of connection to prayer. Dialogic or mystical prayer draws on the imagination. For many of our students prayer that appeals to the imagination is powerfully inspiring. The pray-er experiences deep connection to the Divine feeling like one is in the presence of Hashem or even dialoguing directly with God. For others such prayer is fanciful and ungrounded. We need to develop paths of prayer for the different types of students in our school. In my own experience I can point to students who have grown beautifully through spiritual practice; I have seen others who experienced failure for not feeling a sense of דביקות. 5My anecdotal sense is that this affects young observant men more profoundly than young observant women. As to whether and why that might be so is the topic of a separate paper. That sense of failure can be explained in different ways. The common explanation, which no doubt has merit, suggests that we must do better to inspire and inculcate that feeling of spirituality in our students. But, returning to our models of prayer, we might successfully engage more students in tefila through a deliberate effort to develop distinct paths for mystical prayer, philosophical prayer, dialogical prayer and other forms of prayer. As we will see below, one of the powers of ritual is its capacity to absorb difference through a stable mechanics of practice.

Spirituality-talk can unintentionally give credence to a growing anti-institutional “common sense” regarding traditional, formal religious practice. The last decades of the twentieth century brought a spiritual revival to the Jewish community and well beyond. The increased interest in Kabbalah, Hasidut and the mystical, the development of a neo-Hasidic Modern Orthodoxy in America, and Religious Zionism in Israel are all reflections of this renaissance. This is by no means a particularly Jewish phenomenon. Contemporary spiritual practice is widespread in the form of self-help books, professional workshops and retreats. For the religious person, this should come as welcome news. Spirituality is cool. But we should be careful. Boaz Huss describes a shift that occurred in the meaning and use of the word ‘spirituality’ in the latter part of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first. Understanding what it has meant and how it is used today can help sharpen our goals for our students and better grasp the challenges involved in achieving them.

Huss draws attention to a change that took place in the latter part of the 20th century and into the 21st. Until then, religion and spirituality were connected terms both contrasted with the secular. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the spiritual referred to the immaterial, the metaphysical, that which was beyond what we could see and touch. “Spirituality was connected to the religious, metaphysical, moral, subjective, private, and experiential realms of life and juxtaposed to the physical, material, public, social, economic, and political arenas.”6Boaz Huss (2014) Spirituality: The Emergence of a New Cultural Category and its Challenge to the Religious and the Secular, Journal of Contemporary Religion, 29:1, p. 49. In this sense, the spiritual is the core of the religious experience. It is an aspect, perhaps the central aspect, of religion. All of this is in contrast with ‘the secular’. In this period, to be religious is to believe in and to experience that which is beyond the here and now, the physical, the seeable and the measurable. The spiritual is the term ascribed to matters of the spirit, to things that extend beyond the physical, the immanent and the manifest.

Huss suggests that in the last half century, there has been a significant discursive shift in the use of the term spirituality. “The recent understandings and applications of the term are closely related to New Age culture. The main characteristics of the New Age, as defined by scholars, include the expectation or experience of profound transformation, an inward turning in search for meaning, and the sacralization of the self.”7Ibid, p. 50. The key terms in this description are “inward turn” and “sacralization of the self.” Contemporary spirituality has become a personal affair and closely connected with contemporary psychology. Previously, “the religious” was contrasted with “the secular.” That binary formulation highlights the difference between believing in and experiencing that which is beyond the physical, experiencing the mystical and matters of the spirit on the one hand, and, on the other, believing that only the material and empirical are real. But the discourse has shifted. “The binary opposition between the spiritual on the one hand and the corporeal and material on the other has become blurred in the current definitions and usages of the term; instead, a new defining dichotomy has emerged, juxtaposing spirituality with the category it was previously closely related to: the religious.”8Ibid.

In that contemporary discourse, religion connotes the institutionalized aspects of spirituality. Religion is formal, organized, and rigid. Spirituality is personal, unmediated and fluid. Contemporary spirituality practices are sometimes, but by no means always, connected to religious practice. Spiritual practice includes physical health practices, yoga, gardening, martial arts, meditation and psychology. These can be referred to as spiritual practice in contemporary discourse whether or not God plays a role in the practice. As the anthropologist Robert Wuthnow wrote, “the most significant impact of the 1960’s for many people’s understanding of spirituality was a growing awareness that spirituality and organized religion are different and indeed, might run in opposite directions.”9Wuthnow, Robert. After Heaven: Spirituality in America since the 1950s. Berkeley, CA: U of California P, 1998, p. 72. Wuthnow claimed, and Huss agrees, that contemporary spirituality is contrasted with organized religion. Key to spiritual development is the freedom of the individual to turn inward and to find meaning on his or her own terms, without being confined by the formalities and rigid expectations of institutionalized religion. In contemporary thinking, religion can serve as the path towards spiritual growth. But it might not. And, in fact, organized religion might hinder one’s personal spiritual growth in this sense. The societal understanding of spirituality actually generates a complex expectation and can also serve as a challenge to our traditional practices and pathways to prayer.

This analysis can help us gain insight into the struggles that some of our students experience. We are accustomed to thinking that religion creates a space for personal spiritual growth; that religion and spirituality work towards the same goals and are mutually reinforcing. However, for many, this might not be the case. For these students, institutionalized religion creates a mediated experience of the spiritual. The details and specifications of ritual practices might be seen by our students as an extra step: a means to an end at best, and perhaps an obstacle to achieving the unmediated spiritual experience that they seek. If this is so, for students who connect to the most popular Jewish modes of prayer (e.g, theurgic and mystical), their spiritual and religious energies align and they can achieve and grow. For others, the misalignment leaves students confused and without a clearly articulated alternate path.

One response to this problem is to limit our focus on formal practice and expand spiritual opportunities in the hope that our students can better connect to God and cultivate that aspect of their being. In adopting this strategy, one is unwittingly reinforcing the contemporary dichotomy between the spiritual/personal, and the religious/institutional. But a significant aspect of Jewish life is the collective, embodied practices that should shape our religious experience. These formal practices can serve as entry points to the varied models of prayer. To return once again to our models, philosophical prayer draws on ethical more than imaginative thinking. Spiritual prayer often engages the imagination and the emotions of the pray-er. The embodied rituals of institutionalized prayer can support different styles of personal engagement. In that spirit, I would like to elaborate the power of the formal behavioral and textual aspects of tefila.

4. Ritual: Consciousness, Communication and Continuity

We are trained from a young age to understand mitzvah as obligation and its performance as obedience to God’s word. Ritual theory can deepen our understanding of how mitzvot shape our moral lives, our ethos, by focusing on the social and the (both horizontal and vertical) communicative power of ritual practice, and the significance of our interaction with the rituals themselves. The actions that we perform are embodiments of beliefs and values. When we perform a ritual, we take ideas and make them concrete; in a sense, we bring them to physical life. In addition to its embodying character, rituals are also a form of communicative action. In physically enacting our values, we communicate that commitment to God; at the same time, we communicate that commitment to others through our actions as well. When performed in a communal setting, ritual generates a sense of shared beliefs, values and commitments. Ironically, the expressive and communicative power of ritual derives precisely from the formal, unvarying, communicable nature of ritual action, the aspect that can be most frustrating for today’s high school students.

Roy Rappaport, compellingly arguing that ritual and religion are foundational aspects of what it means to be human,10Rappaport, Roy. Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity. Cambridge University Press, 1999. See Appendix A for a summary of some of the elements that give ritual practice its power. articulates the defining features of ritual. Taken together, they describe the mechanics of rituals, what makes them work.

Rappaport asserts: acceptance is intrinsic to every ritual performance (to every mitzvah) that we do. But, as he stresses, acceptance is not belief. Acceptance is “a public act, visible to both witnesses and to the performers themselves.”11Ibid, pp. 119-120. While it does not attest to what I am experiencing internally, it expresses some level of membership in the community and shared understanding. With that in mind, we can begin to consider the significance of nuances of behavioral distinctions when one performs a mitzvah.

Let us consider the example of standing for קדושה. A person conveys different degrees of enthusiasm and investment by standing up energetically how one places his feet during קדושה the style in which one raises her heels at the proper moments of קדושה. Through each of these junctures one can express levels of investment or resistance. Internally one might feel connected and find meaning in the action. Alternatively one might perform the action out of respect for a parent or teacher – or even be comfortable mindlessly performing the rote behavior. On different days or even at different moments within the same tefila one can interact differently with the ritual. The halakhic behavioral expectation is uniform but the performance is not. At the same time the formality and invariance of the act allows the value to be transmitted on some level and remain intact despite this internal variability. The consistency of the performance creates shared behavioral language and continuity of expression at the same time that it ideally allows for different ways for internal personal interaction with the ritual. It allows for intergenerational continuity and stability despite or in addition to internal individual variability.

When considering halakhic performance in terms of obedience and disobedience, it is a one-dimensional act. God or the rabbis have prescribed a behavior, and we have either followed the instruction or we have not. This is true, but it is not the whole story. These acts are multi-dimensional. In embodying our beliefs and commitments through action, we communicate with the Divine, with each other and with ourselves in rich and complex ways.

Another example of physical expression of prayerful engagement is the recommendation to take three steps back when completing the amida. The Talmud teaches:

.אמר רבי אלכסנדרי אמר רבי יהושע בן לוי: המתפלל צריך שיפסיע שלוש פסיעות לאחוריו ואחר כך יתן שלום

R. Alexander taught in the name of R. Yehoshua ben Levi: one who prays must step back three steps and afterwards offer farewell.12Yoma 53b.

This recommendation is appropriated from other interpersonal contexts. When departing from before royalty, one commonly stepped backwards. When leaving the Temple, one did the same. Clearly, the halakha suggests reenacting common human interaction to shape the interaction between the pray-er and God. In the context of the amida, however, there are no other players. God Himself is not apparently present. Through our behavior, we enact and embody an experience. Considered this way, some people might naturally experience prayer as direct communication with God and such formal departure might feel natural. But even for those people, this is a religious behavior that requires teaching and practice. As with all practices in all disciplines, some students will relate to it quickly and draw meaning from it; others might require more practice; still others might struggle with embodying the human-divine relationship in that way. For all, it takes understanding and then conscious practice for the behavior to be truly embodied. As important as it is to find informal or contemporary ways to experience the spiritual, we should think of our own physical expressions as vehicles for cultivating such inner awareness of the Divine.

5. Connection, Communication and Continuity Through Ritual

We are now better equipped to consider the richness and complexity that occurs during any single ritual act whether bowing at מודים or putting one’s feet together and reciting קדושה. Multiple things are occuring at any such moment. In performing a ritual I say something to and about myself and communicate with others about my relationship with the mitzvah and with the Divine. Although the internal content can vary the ritual performance is an expression – and actually an expression of some degree of acceptance. This can help us appreciate the importance of ritual behaviors as we consider our religious practice over time.

As we continue along life’s journey, we are shaped by our relationships and experiences; our understandings of the world change; we find meaning in different ways and from different things. This is true on an individual level, and the same holds for our larger community. Our Jewish community has changed dramatically over years, decades, and centuries as it moved from one culture to another and from one country and even continent to another. The characteristics of ritualized texts and practices described above communicate the ‘eternal’ nature of our religion, offering stability, continuity and a means of communal connection. At the same time, individuals and even whole communities are able to interact with these ‘eternal’ sets of practices in individualized ways, reflecting the individual’s disposition on a given day and the distinct characteristics of a particular Jewish community during a particular time.

For ritual performance to be a source of communal stability as well as an opportunity for individual expression within the ritual, we must develop opportunities for us and our students to practice drawing meaning from the practice. We must provide coaching for our students and for ourselves. Under the leadership of Rabbanit Lisa Schlaff, and developed through an extensive training program with Lifnai v’lifnim, designed by Rabbis Dov and Yishai Zinger, our students participate in Student Va’ad. Va’ad provides a space for students to connect with their spiritual selves. The Va’ad program could focus on certain embodied practices of daily tefila, providing an opportunity for students to personalize practices. We have mentioned standing with feet together, raising heels during kedusha and rising for kaddish as examples of such embodied practice. We should provide opportunities for students to think about and to bring their feelings to those practices. What did Chazal have in mind in requiring such action? What does it mean to me? If I have not thought much about it, can we work together to fill such behavior with personal meaning?

In that spirit I will mention two other performative actions for consideration – and to help us imagine providing space for group discussion and personal practice. The שולחן ערוך strongly recommends having a מקום קבוע a set place to daven. Most students do de facto have a set space when they daven in school. That is a practice of convenience or consistency but not one that is imbued with the meaning that the halakha intended. Va’ad can provide an opportunity for each individual to personally consider the significance of having a personal space. In what ways is that significant to my experience? Where else in my life do I have set spaces? What do I like about those spaces? What might it suggest in the davening space? What might I do to imbue my personal physical space with meaning each morning? When I consider the ‘set spaces’ in my home I realize that different spaces bring different meanings and experiences. I sit at my kitchen counter with a cup of coffee when I learn a new sugya with the mental space that comes with new beginnings. I realize that I sit in a different seat in my home when I am attending a zoom meeting or teaching. I have yet a different space when I read a magazine or a sefer just for pleasure. I don’t do this intentionally. It has evolved. How do I feel about my davening space? Why did I choose it? How does it make me feel? Am I satisfied with that or do I aspire to a different experience? How might I change the experience? Va’ad provides an opportunity to bring my emotional self to these practices – and to actually perform a daily practice with intention for when I often don’t have the mental space to do so in the rush of the everyday.

Another practice to consider is נפילת אפיים falling on our face. Chazal clearly intended for us to daven in three distinct positions – sitting standing and falling on our face. For many tired students those few moments are a precious time to just put one’s head down and rest for a minute. But Chazal intended something deeper. What is the emotion that is represented in such an action? It would be fascinating to hear the various understandings of the students and adults in the group. Are there patterns? Wide agreement or significant variation? Each person could explore that feeling. For me falling on my face represents an extreme feeling of helplessness and dependence. Such an expression would be fitting – to me – when something is out of my control and I am in need to help. When have I felt like that? Do I experience that every day? Perhaps if I brought that intention to the performance each day I would remember the parts of my life where I do feel the most dependent. And that would become a moment of deeper more focused prayer a tefila that grows out of an awareness of the connection between body and mind that is expressed through falling on my face.

I deeply enjoy the meaning that comes from ritual performance. I enjoy the routine aspects of it and I appreciate the varied possibilities that come with consistent practice. When I travel anywhere in the world and know that all Jews share versions of the same siddur, that we daven in similar ways, that I can connect with any Jew through these practices, I experience it as a miracle of the Jewish people that has been generated through the power of ritual. These practices have kept the Jewish people connected across time and space. When I share these thoughts with my students, they tend to vigorously agree that those shared experiences happen because of the power of our ritualized texts and performances. Both young and old are able to see that power, when we bring it to consciousness. We should explore how to best use this power for our personal growth and our collective strength.

Appendix A

The anthropologist Roy Rappaport, as reflected in the title of his classic work, sees the development of religion and ritual as the essence of what it means to be human. In attempting to express the power of ritual, Rappaport articulates the basic elements of how rituals work. I will briefly summarize his description below.

Encoding by other than performers – a ritual is a behavior that has been established by others at a different time and is meticulously followed now. “A ritual which has never been performed before may seem to those present not so much as a ritual as a charade.”13Rapaport, p. 32. Much of the power of ritual is rooted in the decision to participate, to be included through action, in this act that has a history that precedes me.

Formality – ritual acts take specific forms. They are performed in specific contexts, in a predetermined manner and often at precise times. The specificity of form of the behavior signals that this action or speech is to be distinguished from ordinary action or speech.

Invariance – Rappaport emphasizes that rituals are “more or less” invariant. This is of great significance for understanding the way that rituals work. On the one hand, invariance is essential to establishing the behavior as a ritual. It must be enacted in a precise way. At the same time, it is likely that two people performing the same ritual will also exhibit certain differences in their performance. As an example, each of us might bow at certain moments in the recitation of the Amidah. However, each will differ in how far they bend, for how long and the sort of intentionality they exhibit when they bow. The play between the basic invariance on the one hand and the slight displays of individualism on the other – the “more or less” of the invariance – is an expressive moment of great significance and meaning.

Performance – “Unless there is a performance, there is no ritual.”14Ibid, p. 37. Rituals are embodied beliefs and values. Through the behavior we express ideas. The act is a performance even if I am alone. It is an act before God even when I am alone. The commitment to the behavior even when I am alone reflects the invariant and formal nature of the ritual. It is certainly a performance when I am in the presence of others – with a צבור for example.

In a culture that prioritizes authenticity and an internal feeling of truth the notion of performance might seem inauthentic or shallow. Considering performative behavior from the perspective of ritual theory highlights the power of embodying our values of concretizing our commitments through action. This offers an interesting entry point to the significant Talmudic literature that explores the relationship between intention and action (כוונה and מעשה). We often engage this lomdus as an exploration of which of these two aspects of a mitzvah is primary. Seen from the perspective of ritual theory we can appreciate the distinct role of each and the way that they can reinforce each other..

Ritual as Communication – “Special times and places may, like extraordinary postures and gestures, distinguish ritual words and acts from ordinary words and acts…The designation of special times and places for the performance of ritual also, of course, congregates senders and receivers of messages and may also specify what it is they are to communicate about. In sum, the formality and non-instrumentality characteristic of ritual enhances its communicational functioning.”15Ibid, pp. 50-51.

Ritual performance is an act of communication. Through our actions, we publicly express our commitment in the presence of others. Perhaps more precisely, we share with others that we have made certain commitments. Even when alone, we are expressing a commitment to our own self through the performance of the mitzvah. Through communal prayer, we express our own beliefs and commitments, and are witness to others’ expression of those beliefs and commitment. In so doing, we create shared language and a sense of connection.

- 1The following section draws on an essay by Shalom Rosenberg

תפילה והגות יהודית – כיוונים ובעיות בתוך התפילה היהודית – המשך וחידוש רמת גן - 2פירוש שיר השירים לרבינו עזרא ח See

- 3T.M. Luhrmann, When God Talks Back. New York, Vintage Books, 2012.

- 4https://cct.biola.edu/pray-in-this-way-tanya-luhrmann-on-the-sociology-of-prayer, accessed February 6, 2022.

- 5My anecdotal sense is that this affects young observant men more profoundly than young observant women. As to whether and why that might be so is the topic of a separate paper.

- 6Boaz Huss (2014) Spirituality: The Emergence of a New Cultural Category and its Challenge to the Religious and the Secular, Journal of Contemporary Religion, 29:1, p. 49.

- 7Ibid, p. 50.

- 8Ibid.

- 9Wuthnow, Robert. After Heaven: Spirituality in America since the 1950s. Berkeley, CA: U of California P, 1998, p. 72.

- 10Rappaport, Roy. Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity. Cambridge University Press, 1999. See Appendix A for a summary of some of the elements that give ritual practice its power.

- 11Ibid, pp. 119-120.

- 12Yoma 53b.

- 13Rapaport, p. 32.

- 14Ibid, p. 37.

- 15Ibid, pp. 50-51.