It’s Personal: Teaching the Sugya of מצוה בו יותר מבשלוחו

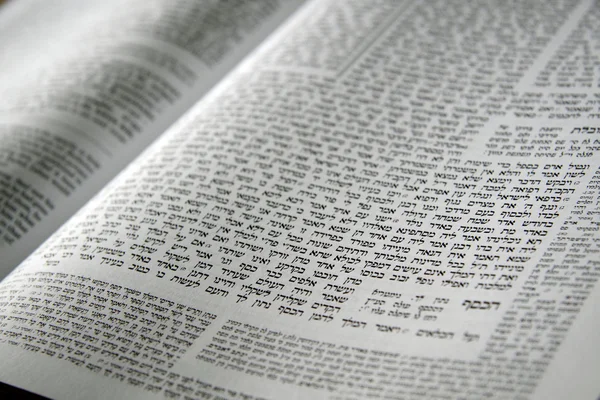

הַשְׁתָּא בִּשְׁלוּחוֹ מְקַדֵּשׁ בּוֹ מִיבַּעְיָא?! אָמַר רַב יוֹסֵף: מִצְוָה בּוֹ יוֹתֵר מִבִּשְׁלוּחוֹ. כִּי הָא דְּרַב סָפְרָא מְחָרֵיךְ רֵישָׁא רָבָא מָלַח שִׁיבּוּטָא. אִיכָּא דְּאָמְרִי: בְּהָא אִיסּוּרָא נָמֵי אִית בֵּהּ כִּדְרַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר רַב. דְּאָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר רַב: אָסוּר לָאָדָם שֶׁיְּקַדֵּשׁ אֶת הָאִשָּׁה עַד שֶׁיִּרְאֶנָּה שֶׁמָּא יִרְאֶה בָּהּ דָּבָר מְגוּנֶּה וְתִתְגַּנֶּה עָלָיו וְרַחֲמָנָא אָמַר: ״וְאָהַבְתָּ לְרֵעֲךָ כָּמוֹךָ״. וְכִי אִיתְּמַר דְּרַב יוֹסֵף—אַסֵּיפָא אִיתְּמַר הָאִשָּׁה מִתְקַדֶּשֶׁת בָּהּ וּבִשְׁלוּחָהּ. הַשְׁתָּא בִּשְׁלוּחָהּ מִיקַּדְּשָׁא בָּהּ מִיבַּעְיָא?! אָמַר רַב יוֹסֵף: מִצְוָה בָּהּ יוֹתֵר מִבִּשְׁלוּחָהּ. כִּי הָא דְּרַב סָפְרָא מְחָרֵיךְ רֵישָׁא רָבָא מָלַח שִׁיבּוּטָא. אֲבָל בְּהָא אִיסּוּרָא לֵית בַּהּ כִּדְרֵישׁ לָקִישׁ דְּאָמַר רֵישׁ לָקִישׁ: טָב לְמֵיתַב טַן דּוּ מִלְּמֵיתַב אַרְמְלוּ.

I imagine someone approaching a student in my 10th grade class in late fall and asking them, “what sugya are you learning in Gemara?” Teachers must practice this exercise with younger Gemara students so that they are always able to answer that question without hesitating. In this instance, the student would respond, “we are learning the sugya of מצוה בו יותר מבשלוחו.” If the conversant had basic familiarity with well known shas concepts, they would presume that we were exploring the parameters of fulfilling personal mitzvot through a shaliach a messenger. This would be a fair assumption. The concept of מצוה בו יותר מבשלוחו is the focus of many shiurim and has practical applications regarding many mitzvot such as brit milah, mechirat chametz and tzedakah, among others. However, our high school Gemara classroom focuses on the sugya, the specific unit of Gemara that does not span the shas but is local, and it has a beginning, an arc and a conclusion.

Often, the dynamism of the sugya itself is set aside as the teacher chooses to expand the shiur beyond the sugya to, instead, explore the lomdus of the shas concept. For example, in a classic Gemara shiur, I could study the text of the Gemara, learn Rashi and Tosafot (in this instance, they are relatively technical, as Tosafot go) and then delve into the central topic in the sugya מצוה בו יותר מבשלוחו. In a classic shiur exploring this concept a number of standard questions would be raised:

- Does the rule apply to all mitzvot or only to a subset of them?

- If I have the choice whether to perform the mitzvah myself in a more rudimentary way or ask a shaliach with expertise (for example, a professional mohel to perform a brit milah) does this rule take primacy over the idea of הידור מצוה or does the quality of the performance take precedence?

- Is kiddushin in fact a mitzvah? What is at the root of that debate?

- Does the rule of מצוה בו apply to preparations for the mitzvah (הכשר מצוה) as well as the mitzvah itself? For example does halakha recognize and prefer that I build my sukkah myself?

These issues can be explored through the many shiurim that build on these core questions and on each other. I love the lomdus as well as a sharp nafka minah that highlights the sides of the question. But what about the sugya itself?

When we focus intensively on the sugya itself, we often find that the sugya is pursuing an argument of its own, with many moves and countermoves that often offer a distinct conception of the topic at hand. In this sugya of מצוה בו יותר מבשלוחו studying the Gemara carefully reveals a dimension of the rule and elements of the entire sugya that are otherwise left unexplored. Personally, I find this the most exciting part of learning Gemara. For my high school students who are still learning how Gemara works, this approach is vital to help them develop an appreciation for the mechanics of a sugya and the capacities to study other sugyot. They must work through the steps of the sugya in order to understand why the Gemara even referenced this particular shas topic at all.

The Question

In order to uncover the broader agenda of the sugya, we must first approach it line by line.

The Gemara begins with a textual question. The Mishnah states האיש מקדש בו ובשלוחו a man can betroth through his own action or that of his proxy. Why asks the Ba’al HaSugya is the word בו necessary in the Mishnah? The purpose of this Mishnah is to teach that kiddushin can occur by proxy. If the Mishnah stated that rule alone האיש מקדש בשלוחו I would still know that a man can perform the betrothal himself from all that I have learned so far in the Masechet. Why then is the word בו included in the Mishnah?

I am curious what students think of this question. Does it resonate as a strong question? Why or why not? I ask them. Many students say that they like the question. Some students say that they are accustomed to this type of question from their Torah study where they have learned that every word carries meaning and no word is unnecessary: “this is how we study sacred texts.” Some students say that it’s simply intuition; they feel that the word is unnecessary and the question is therefore a good one.1 For still other students, the question does not strike them as meaningful and is rather trifling. Those students suggest that the Mishnah is simply stating its rule fully and clearly: a man can betroth a woman either through his own action or via proxy. Why would we expect the Mishnah to be cryptic rather than clear?

The students’ last question troubled the Ba’alei HaTosafot as well, although they formulated it in Talmudic terms.2 They ask: while the Gemara does often draw inferences from unnecessary words in the Mishnah it also often employs the principle of לא זו אף זו (lit. not only this but also that). The Mishnah will often list two examples the first one is a more basic application while the second example further extends the application of the rule. The לא זו אף זו rule teaches us to expect that the Mishnah will state the halakha in incremental order presumably for the purpose of clarity. The existence of the לא זו אף זו rule prompts the Ba’alei HaTosafot to wonder why the Gemara considered the word בו to be unnecessary and requiring explanation. Could not the inclusion of the word בו be explained by the לא זו אף זו principle?

This type of “question on the question” runs through the minds of our students (and perhaps teachers) very often. Our students would not think of the question in Talmudic language, but their question is the same as that of the Tosafot.3 I suspect that they have become so acculturated to the Gemara asking this type of question that they don’t think to raise this “question on the question” in class. They need to be encouraged to do so, and we have to set the stage for that question to be aired. To facilitate that, I either incorporate the idea of the Tosafot or actually learn the text of the Tosafot, depending on the energy and focus of the students in the classroom at the time.4

השתא בשלוחו וכו׳. בכמה מקומות שונה לא זו אף זו

ואין התלמוד מדקדק. וכאן הואיל ויודע טעם מפרש.

The Tosafot HaRosh suggests that although the Gemara often invokes the לא זו אף זו principle in this instance the Ba’al HaSugya does not invoke that principle because he has something specific to teach us. The sugya cites the question precisely in order to provide a context for the answer. In order to present Rav Yosef’s teaching the Ba’al HaSugya asked the textual question to which Rav Yosef would provide an answer. He uses the language of the Mishnah as a support or proof for the ruling of Rav Yosef that מצוה בו יותר מבשלוחו simultaneously answering the question and teaching the principle.

The suggestion of the Rosh opens a space for interesting deliberation among teachers about how to explain this idea to students. It appears that the Rosh is saying that the Ba’al HaSugya does not think that this is a strong or “real” question nor was the Mishnah necessarily written with an intent to convey this inference. If this is the case, how do we explain the intent of the Ba’al HaSugya in asking this question?5 Should we infer that this sugya is an intentionally constructed dialogue premeditatively designed to make a specific point?6 Such discussions offer students the opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of the mechanics of Gemara, skills they can transfer to other sugyot.

Furthermore, we can see that challenging the assumptions of the text in this way and asking the intuitive questions that arise for the student can help reveal the nuances and dynamics of the text. Imagine if the sugya did not begin with the textual question regarding the word בו. Instead imagine it simply stated אמר רב יוסף מצוה בו יותר מבשלוחו. Rav Yosef states that the preferred option is for the man to perform the betrothal himself. Written this way we might plausibly conclude that Rav Yosef offered this comment on the Gemara as an independent value statement not rooted in or dependent upon the language of the Mishnah nor in response to the question that the Gemara poses. Imagining this when we reread the Gemara we realize that Rav Yosef likely did not himself ask the question. The anonymous Ba’al HaSugya asked the textual question on the Mishnah and in so doing prepared the reader to discover that Rav Yosef’s ruling had a textual basis in the Mishnah. The reader is left wondering: did Rav Yosef offer this halakha as a free-standing statement of value and practice? Was he suggesting this as an interpretation derived from the language of the Mishnah?

Based on the Rosh we can propose the following steps in the development of this idea. First Rav Yosef expressed the value of מצוה בו יותר מבשלוחו as the preferred way to perform kiddushin. Subsequently the Gemara provided support for the rule through its close reading of the Mishnah. The Ba’al HaSugya asked the textual question because it sought to teach us that Rav Yosef’s rule has textual support in the language of the Mishnah in the seemingly extra word בו.

We are left to consider: why did the Ba’al HaSugya want to find support for Rav Yosef’s rule in the words of the Mishnah? Why does that not appear to have been necessary for Rav Yosef himself? While we cannot draw any conclusions, these questions push us to consider the relationship between textual authority and personal authority, the possible differences in perspective that existed between the generations represented within the Gemara, and the relative authority of the Tannaim and Amoraim.

Unpacking Rav Yosef’s Rule7

Let’s turn to the rule itself. What is Rav Yosef teaching us? Sometimes, when we encounter a well-known principle in the Gemara, the reader of the Gemara finds it difficult to allow the text of the Gemara to speak in its own words. Our prior assumptions and understandings can make plain meanings of the Gemara less accessible. We must make a conscious effort to “unread” the Gemara so that we can encounter the text anew.

Our principle of מצוה בו יותר מבשלוחו is a good example. Reading through common halakhic texts we find this principle applied to all mitzvot.8 Whenever one has the opportunity to perform a mitzvah, they should ideally perform it physically rather than delegate its performance to someone else even though the mechanism of shelichut would nonetheless ensure that the “credit” is applied to the principal who appointed the Shaliach.

This interpretation of the rule is drawn from a simple reading of the Gemara with an assist from Rashi. To the citation of Rav Yosef Rashi adds דכי עסיק גופו במצות מקבל שכר טפי because when his body is involved in the performance of mitzvot he receives greater reward. Rashi applies the principle of Rav Yosef regarding kiddushin and applies it to the performance of any mitzvah. Rashi interprets Rav Yosef’s statement as implied by the context of the sugya. The complete sentence reads

אמר רב יוסף מצוה בו יותר מבשלוחו כי הא דרב ספרא מחריך רישא רבא מלח שיבוטא

Said Rav Yosef, is it a mitzvah with his body more than with his proxy, like this (case) that Rav Safra charred the head, Rava salted the fish.

It is greater for the man to betroth the women personally just as we find that the great Amoraim Rav Safra and Rava personally engaged in preparations for Shabbat. Rashi reads the Gemara’s sentence in a maximalist way. The principle is articulated and then expanded via the example from Shabbat. Through these examples, the rule is shown to extend to the performance of any mitzvah.9 This reading of the Gemara is most common and is the one that is followed in halakha.

However, if we return to the Gemara and read it without preconceptions, we are able to draw a different understanding of Rav Yosef’s ruling and the agenda of the sugya overall. First, in order to understand what Rav Yosef meant, we must identify precisely the words that Rav Yosef himself said. In class, I ask the students to use quotation marks to highlight Rav Yosef’s words. I am asking them to identify precisely which words in the Gemara were said by Rav Yosef and when the Ba’al HaSugya took over.

Most students are inclined to place the entire sentence in quotes noting that his words begin after אמר רב יוסף and conclude at the key words איכא דאמרי. They have been trained that איכא דאמרי indicates a new sentence. While I confirm the validity of that answer I also suggest that another possibility exists. Because I prompt them they take another look. A few students will suggest that Rav Yosef only said the words מצוה בו יותר מבשלוחו; the students are able to identify that possibility although they are usually not immediately sure why one would suggest that. I pause for a moment to allow the two possibilities to sink in and say “Read the sentence again closely. What evidence could you bring to support the latter reading in which Rav Yosef said the principle alone without the comparison to Shabbat?” After a few seconds a small number of students will raise their hands noting the change of language from Hebrew to Aramaic in the middle of the sentence! The students are now able to see interesting temporal possibilities within this one line of the Gemara:

Option 1: Rav Yosef articulated the principle of מצוה בו יותר מבשלוחו and he himself brought support for that idea from Rava and Rav Safra’s Shabbat preparations.

Option 2: Rav Yosef articulated the principle of מצוה בו יותר מבשלוחו. The Ba’al Ha’Sugya then offered support for Rav Yosef’s statement by citing the pre-Shabbat routines of Rava and Rav Safra.10

Is this a distinction without a difference? Why does it matter if Rav Yosef himself made the comparison to Shabbat preparations or if someone else drew that comparison? The Gemara is making the same claim according to either option.

To help students process this question, I ask them to once again consider Rav Yosef’s principle. When I prepare for class, I play out this conversation in my mind:

Teacher: What will be achieved or improved by the man doing this himself rather than via proxy?

Student: The man will benefit because מקבל שכר טפי he will receive greater reward from God. (They remember Rashi).

T: So why is it better to do the mitzvah yourself? Who benefits from that?

S: It is better for the person if he does the mitzvah himself because of the reward he will receive.

T: According to that logic, what mitzvot would this principle include?

S: Any mitzvah. It’s better if I do it myself.

T: Let’s imagine that Rav Yosef himself did not mention anything about Shabbat. If you read the statement without the comparison to Shabbat, who is the beneficiary, and what will be achieved?

S: If I read the Mishnah and then I read Rav Yosef’s statement, it sounds like Rav Yosef is teaching something specifically about marriage; that it is better for the husband to perform the kiddushin himself than to do so via proxy.

T: What is Rav Yosef trying to tell us through that teaching? Why would it be better for the husband to perform the kiddushin himself rather than through a shaliach?

S: Rav Yosef encourages a personal interaction between the man and the woman rather than between a spouse and a proxy or between two proxies. The kiddushin becomes more personal and less transactional.

According to this reading of the Gemara, Rav Yosef’s teaching focuses on the performance of kiddushin and not of any other mitzvah. Rav Yosef sought to ensure that marriage took place in a personal fashion between the couple themselves. According to this interpretation, Rav Yosef did not articulate a general principle about mitzvah performance. To emphasize that point, we check the Mesoret HaShas for parallel citations.11 Notably we do not find this phrase cited anywhere else in the Talmud. The term מצוה בו יותר מבשלוחו is found only here in the context of kiddushin. Considered in this way, we can say that, according to Rashi, this principle is about the human-God relationship in the performance of mitzvot. According to the plain reading of his words, Rav Yosef was focused on the husband-wife relationship. These two values are not in conflict. But they are different possible dimensions of the principle.

How do we understand the Gemara according to each of these possibilities? Rashi chose to explain Rav Yosef’s statement based on the complete sentence as found in the Gemara. Rashi interprets that the Gemara’s parallel to Shabbat preparations implies that the principle should be expanded to all mitzvah performances. In other words, even if we are correct that Rav Yosef was referring to marriage, the Gemara puts this idea to use in a maximalist, expansive way. If we read Rambam carefully, we discover, through his precision, that Rambam did not agree. He offered a minimalist reading of Rav Yosef’s teaching. In his view, Rav Yosef was teaching a value about marriage, not a value about the performance of mitzvot. The Ba’al HaSugya then brought the cases of Shabbat preparations as a similar example.

First, let’s look at Rambam’s language in Mishneh Torah. Regarding kiddushin, the Rambam writes:

מִצְוָה שֶׁיְּקַדֵּשׁ אָדָם אֶת אִשְׁתּוֹ בְּעַצְמוֹ יוֹתֵר מֵעַל יְדֵי שְׁלוּחוֹ

12

Rambam has essentially cited Rav Yosef’s statement. It is a mitzvah (an ideal way to perform the mitzvah but not an obligation) for the man to perform the kiddushin himself. Regarding Shabbat preparations, Rambam writes:

אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁהָיָה אָדָם חָשׁוּב בְּיוֹתֵר וְאֵין דַּרְכּוֹ לִקַּח דְּבָרִים מִן הַשּׁוּק וְלֹא לְהִתְעַסֵּק בִּמְלָאכוֹת שֶׁבַּבַּיִת חַיָּב לַעֲשׂוֹת דְּבָרִים שֶׁהֵן לְצֹרֶךְ הַשַּׁבָּת בְּגוּפוֹ שֶׁזֶּה הוּא כְּבוֹדוֹ.

13

Rambam cites the notion of using one’s own person to prepare for Shabbat even if one usually does not perform these tasks and others are to do them in their stead. He gives a number of examples of Amoraim doing such Shabbat preparations themselves. Taking one’s own time to personally engage in preparations for Shabbat is the fulfillment of a mitzvah from the Neviim of honoring the Shabbat שזה הוא כבודו.

For Rambam, kiddushin and kavod Shabbat are comparable but distinct categories. We see this because 1) Rambam does not apply Rav Yosef’s terminology to Shabbat preparations. In each instance, kiddushin and Shabbat, Rambam uses the language of the particular sugya and does not extend the language of Rav Yosef to the laws of Shabbat. 2) Rambam states that kavod Shabbat is an obligation (חייב לעשות) not just optimal behavior. Shabbat is not an expansion of Rav Yosef’s rule. It is a similar but distinct concept that exists regarding the laws of Shabbat.14

Marriage by Proxy?

By this point, a student has likely raised the question of why one would want to perform kiddushin through a shaliach at all! To our students’ instincts, this is an odd practice. The question provides an opportunity to reinforce that the reasons for and history of marriage are varied. Since historically, marriage was often for political alliances between royal or noble families, the distance might have been an obstacle while the marriage was still necessary. In fact, messengers were often sent to negotiate the marriage alliances. Aside from these political or legal reasons, geographical barriers, business travel, or military service were also circumstances that necessitated that a marriage take place via proxy.15

A number of studies trace and document these practices to the Medieval period. Our students have also learned of marriages as an element in establishing peaceful relations and alliances between families and political forces. When this is brought into the discussion of the sugya, students are more easily able to situate this Mishnah and sugya into a context of social meaning. While we can understand how marriage via proxy came to be and why it was considered useful and even important, we would not see this as a positive practice. The student can understand that kiddushin by proxy is valid (Mishnah) but is a matter of concern for the Gemara. Kiddushin, our rabbis thought, should be a more personal and intimate matter.

A Second Version

The Gemara cites a second interpretation to tackle the question of the extra word/s in the Mishnah (איכא דאמרי).16 Rav Yosef clearly based his statement on the language of our Mishnah as evidenced by the focus on the case of שליח. Nonetheless the Gemara suggests that we cannot draw textual support for Rav Yosef’s idea from the reisha of the Mishnah. There is an alternate possibility for the Mishnah’s emphasis on the man performing the kiddushin himself based on a related but different ethical priority of marriage.

Rav Yehuda cites Rav: a man who performs kiddushin without first seeing the woman violates the mitzvah of ואהבת לרעך כמוך. Because this is a matter of איסור and not just מצוה (a violation and not just preferred behavior) it is a more immediate priority when interpreting the text. Therefore the second interpretation concludes that the word בו in the first statement indicates Rav’s rule while the word בה in the second statement teaches Rav Yosef’s rule.

This suggestion of the Gemara raises three sets of questions:

1. Why does the Gemara assume that Rav’s statement (אסור לאדם שיקדש את האשה עד שיראנה) is a stronger “interpretation” of the first segment of the Mishnah than Rav Yosef’s statement (מצוה בו יותר מבשלוחו)? It might be more justifiable to infer Rav Yosef’s statement from the Mishnah for two reasons: 1) the value of מצוה בו applies in all cases of kiddushin while Rav’s rule is limited to a case where the husband has never seen the future wife. Rav Yosef’s rule is therefore a more inclusive rule.17 2) Rav Yosef is clearly commenting on our Mishnah discussing the case of a שליח while Rav’s statement is a general teaching and not rooted in our Mishnah. Why would we opt to interpret the Mishnah in accordance with Rav’s law?

2. Students will, of course, ask a more basic question: who gets married without seeing their prospective partner first? Why would someone do that? This is a romantic moment, bringing two people together in shared commitment, and should never happen through a proxy and certainly not without first determining that the couple is compatible with each other!

3. Perhaps even more fundamentally, the entire sugya seems to run against the language of the Mishnah itself! The Mishnah states האיש מקדש בו ובשלוחו without hesitation. As Tosafot notes,18 this language of the Mishnah suggests that it is entirely permissible (לכתחילה) to perform kiddushin by proxy.19 Yet, the sugya is clearly trying to limit the use of the shaliach and suggests that kiddushin through a shaliach is not ideal.

To help clarify the relationship between the halakha of the Mishnah and the agenda of the sugya, I will draw on Meir Dan-Cohen’s distinction between conduct rules and decision rules.20 Dan-Cohen traces the original question back to Jeremy Bentham. Bentham posited that the law that communicates a crime (for example, do not steal) is distinct from the law that communicates the punishment for that law (replacing or paying for the stolen object).21 These are not two parts of the same law; rather, these are two distinct laws. Dan-Cohen proposes a categorical distinction between rules that are addressed to the general public and rules that are addressed to the judges. Rules that are addressed to the judges are decision rules. They express the rules and guidelines for the judges’ decisions when matters come before them. Conduct rules are addressed to the general public and provide guidelines for their behavior. These are related but distinct categories.

Dan-Cohen uses criminal action under duress as an example of this distinction. If a person commits a crime under duress, a judge might decide that the fact that it occurred under duress should serve as a defense for the criminal and minimize or even excuse him from consequences. That is a decision rule. However, this is not to say that one may commit a crime when under duress. The conduct law still stands. One may not steal or murder – even under duress. However, duress might affect the decision rule.22

This distinction between conduct rules and decision rules can help clarify the statement of the Mishnah and the goal of the sugya. The Mishnah teaches the decision rule. Kiddushin performed via proxy is fully valid לכתחילה. The sugya, however, is teaching conduct rules. The sugya recommends that kiddushin should always be performed in a manner that is personal and is a fulfillment of one’s responsibility to the partner. At certain times there is an איסור involved; even when there is no prohibition it is always preferable to perform the kiddushin in person. Still, kiddushin through a shaliach is halakhically valid.

Considering the sugya from this perspective, we can propose that the Gemara’s inferences regarding all three segments of the Mishnah are guided by the same principle. Rambam in his commentary to the Mishnah states this explicitly. He writes:

העיקר אצלנו שלוחו של אדם כמותו והביאו ראיה על זה ממה שנאמר ושחטו אותו כל קהל עדת ישראל (ואע”פ) שמותרת שחיטת כל הפסחים לאחד לפי שהוא שליח צבור אבל הנכון אצלנו שיקדש האדם בעצמו יותר משיקדש לו שלוחו לפי שמעיקרנו לא ישא אדם אשה עד שיראנה לפי שאנו חוששין אולי לא תישר בעיניו ויעמוד עמה ולא יאהבנה וזה אסור לפי שנאמר ואהבת לרעך כמוך ולפיכך הקדים בו על שלוחו ומזה הטעם בעצמו אנו אומרים לא ישיא אדם את בתו כשהיא קטנה עד שתגדיל ותאמר בפלוני אני רוצה ולפיכך הקדים בה על שלוחה

Rambam emphasizes that all of the Gemara’s inferences from the language of the Mishnah (בו בה כשהיא נערה) prioritize the practice of the kiddushin occurring directly between the man and the woman.

Having arrived at this point, we understand that while the Mishnah states that the law permits kiddushin through a shaliach, the sugya has constructed an argument to restrict the use of shlichut for kiddushin. The sugya then reads these conduct rules back into the text of the Mishnah, and these conduct rules get codified as law!

Men, Women and Marriage

The sugya still needs to address the reason for the difference between men and women regarding kiddushin via a shaliach. The Gemara asserted that a prohibition sometimes exists in the case of men but never exists in the case of women (אבל בהא איסורא לית בה). What asks the sugya, is the reason for this distinction?

I tell the students that the sugya will now reference one of the more controversial sentences that one can find in shas – and became particularly controversial in our Modern Orthodox community over the last half century. The Gemara says that the Mishnah is ‘כדריש לקיש’; it follows the view of Reish Lakish that טב למיתב טן דו מלמיתב ארמלו it is better to dwell with another23 than to dwell as a widow. Rashi adds משל הוא שהנשים אומרות על בעל כל דהו. This sentence is an aphorism that women would say regarding “whatever husband.” This brief addition of Rashi becomes very significant for explaining the idea to the students. Rashi notes that although the Gemara states that the Mishnah follows Reish Lakish and cites what he said (כדריש לקיש דאמר ריש לקיש) Reish Lakish is actually citing what women would commonly say regarding marriage. The distinction between a Rabbi saying something about women and women saying something about themselves is of great significance for the students, and rightly so.

The question I ask them is: how did Rashi know that? Did something compel him to explain it this way? Some make a suggestion about Rashi’s time while others respond that hundreds of years divide Rashi and Reish Lakish. I ask them to recite the sentence to themselves and see what they notice about the words. Students notice that it rhymes. I point out the measures contained in the sentence when broken up as follows and read with the bolded syllables emphasized:

טב ל-מיתב-טן דו–מל-מיתב-ארמלו

The sentence has the sound of a rhyming aphorism, a line that women would recite (I imagine them doing so with a bitter sense of irony), acknowledging the reality within which they live. When I ask students why women might feel this way, some students remember the first sugya that we learned together when we focused on kiddushin and kinyan as complementary terms that refer to the intimate and the economic aspects of the relationship respectively. Students recognize that the issue of gender equality as it relates to economics is even today not fully resolved. They can imagine that the economic imbalance was even more pronounced in antiquity.

Once we understand and properly contextualize the term, we return to reread the lines from this perspective. The distinction between men and women regarding a possible issur to marry someone one has not met is meant to respond to reality rather than create a reality. The Gemara is not necessarily saying that women are emotionally different from men, although that is a possibility as well. The Gemara is saying that the situation is different for women and men for a possible range of reasons, and therefore the woman can make that decision herself rather than be further restrained by the law.24

I conclude this unit with a viewing of Chaim Shlomo Mayes performing his wedding song based on this Gemara. Our students enjoy knowing the references, learning a bit of Yiddish, and completing the unit with some celebration. The video is accessible on YouTube.25

We have uncovered in this small sugya, historical layers that reveal a dynamic intergenerational discussion about the nature and purpose of marriage. As part of this discussion, we have explored textual authority vs. personal authority, possible differences between men and women, decision rules and conduct rules, the ideal way to perform mitzvot and the nature of Shabbat preparation. When our students learn such a sugya well, they are strengthening their capacities as Ovdei Hashem and citizens of the world by deepening their understanding of halakhic practice, the dynamics of the sugya, how to best perform a mitzvah, the history of marriage, legal theory, consideration of gender differences, and rabbinic authority. Studied in this way, Gemara provides opportunities for deep development of the characters of its students.

Footnotes

- This can open a discussion comparing Torah and Mishnah. Should we read Mishnah with the same degree of precision as we read Torah? They are both sacred texts but the Torah is divine in a way that the language of the Mishnah is not. See Tosafot Kiddushin 2a ד״ה האשה and Meiri’s response to Tosafot’s comments op cit.

- See תוספות ד״ה השתא and תוספות הרא״ש ד״ה השתא and ריטב״א.

- In my view, one of the core responsibilities of the Gemara teacher today is to translate Talmudic terminology into accessible language so that students can understand the mechanics of the sugya and internalize the Talmudic terminology that conveys those mechanics.

- More often, I do not teach this Tosafot because it is technical in its language.

- By way of contrast Tosafot on the page distinguishes between a case of two phrases and a case of two words. The rule of לא זו אף זו applies to two phrases that are included in a Mishnah and the first phrase seems to be unnecessary. The rule does not apply to two words in the same phrase. Therefore the Ba’al HaSugya’s question is a ‘real’ question. Tosafot’s distinction is difficult to explain. Atzmot Yosef suggests that with two phrases or sentences, one can imagine that the more basic innovation was written first. Subsequently, the greater innovation was added or included and the original sentence was preserved in its original state. However, that time lapse and subsequent chiddush is not reflected nor coherent when found in one phrase.

- Students in this class will have encountered this argument from Rashba’s commentary on Kiddushin 2b.

- This section draws on the work of Dr. Shaul Baruchi in the Gemara curriculum guide designed by Machon Shiluvim at Yeshivat Hakibbutz HaDati for SAR High School, 2007.

- See, e.g, Magen Avraham Orach Chayim, Chayei Adam Hilchot Zehirut Mitzvah 68:3, Sha’arei Teshuva Orach Chaim 250:1:2, Ba’er Heitev 250:1:2, Mishnah Berurah 250:1:3.

- In the Acharonim literature this opens a series of questions that arise from this idea. For example how do we proceed when two principles are in tension? One is obligated to write a Sefer Torah; this is the last of the 613 mitzvot. If I appoint a sofer to fulfill that task the Torah will be significantly more beautiful than if I write it on my own. How do we balance the tension between הידור מצוה and מצוה בו יותר מבשלוחו? Which rule should take precedence? See Chayei Adam, op cit.

- Baruchi, op cit.

- As mentioned earlier, each use of a resource on or off the page of the Gemara provides an opportunity to teach or reteach the proper use of that technology.

- Mishneh Torah, Kiddushin 3:19. The full text reads:

מִצְוָה שֶׁיְּקַדֵּשׁ אָדָם אֶת אִשְׁתּוֹ בְּעַצְמוֹ יוֹתֵר מֵעַל יְדֵי שְׁלוּחוֹ. וְכֵן מִצְוָה לָאִשָּׁה שֶׁתְּקַדֵּשׁ עַצְמָהּ בְּיָדָהּ יוֹתֵר מֵעַל יְדֵי שְׁלוּחָהּ. וְאַף עַל פִּי שֶׁיֵּשׁ רְשׁוּת לָאָב לְקַדֵּשׁ בִּתּוֹ כְּשֶׁהִיא קְטַנָּה וּכְשֶׁהִיא נַעֲרָה לְכָל מִי שֶׁיִּרְצֶה אֵין רָאוּי לַעֲשׂוֹת כֵּן אֶלָּא מִצְוַת חֲכָמִים שֶׁלֹּא יְקַדֵּשׁ אָדָם בִּתּוֹ כְּשֶׁהִיא קְטַנָּה עַד שֶׁתַּגְדִּיל וְתֹאמַר לִפְלוֹנִי אֲנִי רוֹצָה. וְכֵן הָאִישׁ אֵין רָאוּי לְקַדֵּשׁ קְטַנָּה. וְלֹא יְקַדֵּשׁ אִשָּׁה עַד שֶׁיִּרְאֶנָּה וְתִהְיֶה כְּשֵׁרָה בְּעֵינָיו שֶׁמָּא לֹא תִּמְצָא חֵן בְּעֵינָיו וְנִמְצָא מְגָרְשָׁהּ אוֹ שׁוֹכֵב עִמָּהּ וְהוּא שׂוֹנְאָהּ.

- Mishneh Torah, Shabbat 30:6. The full text of the halakha reads:

אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁהָיָה אָדָם חָשׁוּב בְּיוֹתֵר וְאֵין דַּרְכּוֹ לִקַּח דְּבָרִים מִן הַשּׁוּק וְלֹא לְהִתְעַסֵּק בִּמְלָאכוֹת שֶׁבַּבַּיִת חַיָּב לַעֲשׂוֹת דְּבָרִים שֶׁהֵן לְצֹרֶךְ הַשַּׁבָּת בְּגוּפוֹ שֶׁזֶּה הוּא כְּבוֹדוֹ. חֲכָמִים הָרִאשׁוֹנִים מֵהֶם מִי שֶׁהָיָה מְפַצֵּל הָעֵצִים לְבַשֵּׁל בָּהֶן. וּמֵהֶן מִי שֶׁהָיָה מְבַשֵּׁל אוֹ מוֹלֵחַ בָּשָׂר אוֹ גּוֹדֵל פְּתִילוֹת אוֹ מַדְלִיק נֵרוֹת. וּמֵהֶן מִי שֶׁהָיָה יוֹצֵא וְקוֹנֶה דְּבָרִים שֶׁהֵן לְצֹרֶךְ הַשַּׁבָּת מִמַּאֲכָל וּמַשְׁקֶה אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁאֵין דַּרְכּוֹ בְּכָךְ. וְכָל הַמַּרְבֶּה בְּדָבָר זֶה הֲרֵי זֶה מְשֻׁבָּח

- A close reading of Rambam in his commentary to the Mishnah reveals this tension in a textual variant. In R. Yosef Kafih’s edition of the commentary he cites two manuscripts that state וכך הקדים בה על שלוחה לפי שהתעסקות האדם במצוה עצמו יותר שלם מאשר יטיל על זולתו לעשותה לו. This explanation parallels that of Rashi on the Gemara. It is the text that Kafih includes in the body of the Commentary to the Mishnah. In the footnote Kafih cites the Bodleian manuscript: ולפיכך הקדים בה על שלוחה and deletes the next sentence. This is the version that is in the commentary that is printed in our Gemarot. Kafih cannot explain the alignment between this version and the text of the Gemara. Following our reading this version of Rambam is clear. Rambam aligns the reasoning of all three segments of the Mishnah. In each case the Gemara emphasizes the importance of a personal encounter between the husband and the wife prior to kiddushin. See below.

- Retha M. Warnicke, The Marrying of Anne of Cleves, (Cambridge University Press: 2000), Chapter 2.

- The ika d’amri term is used to identify legal variants in the Talmudic tradition, in contrast to v’amri lah or ve’i-tema which record variant attributions. See Yaakov Elman, Orality and the Redaction of the Babylonian Talmud, Oral Tradition 14:1 (1999), pp. 61-64.

- Tosafot and Tosafot HaRosh tackle this question.

- See ד״ה אסור לאדם.

- The Mishnah does not say for example אם קדש על ידי שליח מקודשת which would mean that it is only valid בדיעבד.

- Meir Dan-Cohen, “Decision Rules and Conduct Rules: On Acoustic Separation in Criminal Law,” Harvard Law Review, Jan. 1984, Vol. 97, No. 3, pp. 625-677.

- Jeremy Bentham, A Fragment on Government and an Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, see Dan-Cohen at note 1, p. 626. Bentham’s initial exploration focused on the relationship between the criminal violation and its consequence. For example, murder is a violation of the law. Capital punishment or prison provide possible guidelines for judges when they determine the consequence for the violation. Stealing is a violation of the law. The consequence for stealing is a decision rule that is provided to judges and which they implement. This prompts an important conversation regarding the relationship between the rules given to guide people’s conduct and the judge’s application of the law when it is violated. This relates to the Talmudic sugya of אין עונשין אלא אם כן מזהירין a topic that we will not elaborate on here.

- This distinction can be helpful in explaining Rambam’s view of יהרג ואל יעבור where one can be obligated to surrender one’s life rather than violate the law but is nonetheless absolved of any consequence because it occurred under duress. See Rambam Yesodei HaTorah.

- Rashi translates טן דו as גוף שנים (two bodies) with the word דו apparently deriving from duo. Marcus Jastrow in his Dictionary (p. 540) translates each word differently. The word טן derives from טעון meaning weighty and the word דו is similar to the word דוי (which we recite at sheva brachot) meaning angst. He translates the term טן דו as “with a load of grief.” The aphorism’s intention is “it is better to dwell with a load of grief than to dwell alone.” With this in mind it is noteworthy that the aphorism itself is not gendered and could be equally applied to men and women. The Gemara applies it to women perhaps because women did so themselves.

- I do not reference the debate between Rabbi Rackman and Rabbi Soloveitchik about the nature of the aphorism, whether it is sociological, psychological or metaphysical. For an extended analysis on Tav L’meitav including citations regarding the Rackman-Soloveitchik debate, see Ruth Halperin-Kaddari, Tav Lemeitav Tan Du Milemeitav Armalu: An Analysis of the Presumption, Edah Journal 4:1, Iyar 5764, pp. 1-28, in particular pp. 6-7 and note 28.

- See video here. Accessed July 24, 2024.