Disrupting the Grading Ecosystem

Disrupting the Grading Ecosystem1

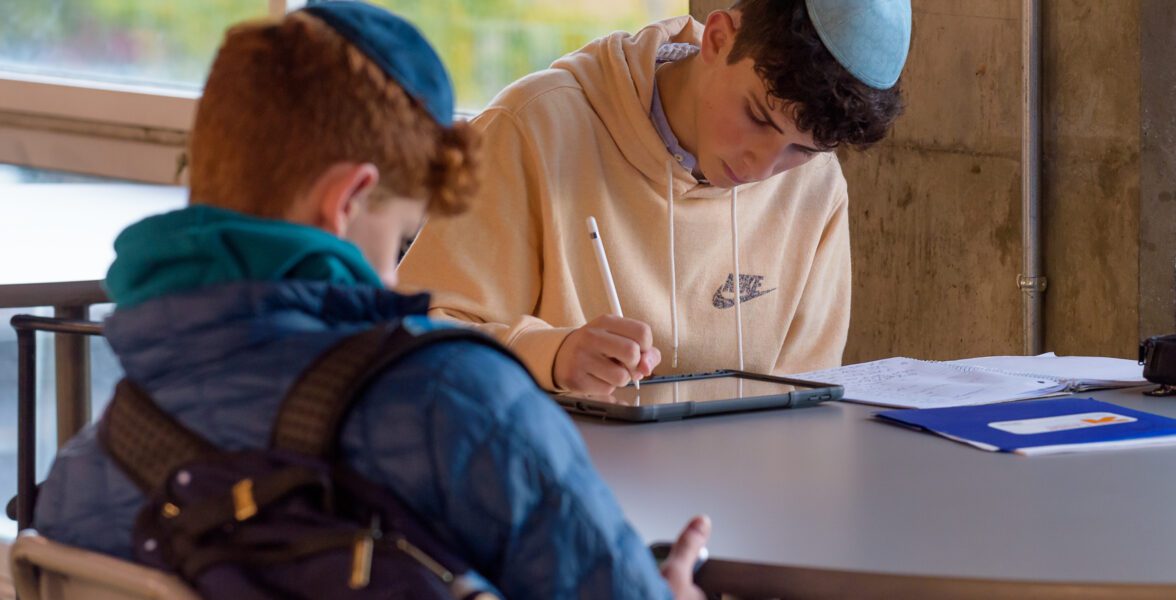

Our school and we are complicit in the stressful culture of American schooling rooted in high stakes grading. Can we act to disrupt the dynamic?

Students today experience a greater sense of anxiety than ever before. Hundreds of articles, op-eds, and essays have been written describing the stress that students experience surrounding school and academic expectations. Ask a student about the source of this stress, and tests and grades will inevitably be central to the response. Such assessment measures are deeply embedded in the infrastructure of our schools, for better and for worse, and they become drivers of much of what happens in school. But we must take a step back and consider these practices. Why do we give grades? When and why did this system originate? Whose needs are served by the process of grading, distributing report cards, and designing transcripts? Before we can posit solutions to this problem, we need to explore the problem itself, understanding its component parts and the values that underlie them.

Some History

Grades are a central component of the schooling experience, so central that it is hard to imagine school without them. When aspects of our experience become reified in this way, we experience them as inevitable, as always having been there. But grading has a history, a story that evolved over time. On American shores, Ezra Stiles, President of Yale University, is credited with creating the first grading scale in 1785. He used four levels, Optimi, Second Optimi, Inferiores, and Pejores. William Farish, a professor of Chemistry at Cambridge in the late 18th century, is credited with inventing “the mark,” an evaluation that would, he thought, be more objective and allow for the ability to evaluate a larger number of students in a shorter period of time. At the time, examinations were still mostly oral and qualitatively assessed. Students expressed concern about the subjectivity of the evaluations. Farish’s ‘marks’ were to serve as a solution to the subjectivity problem. Those “marks” eventually became “grades,” ironically paralleling the objective system of evaluating the quality of various products sold on the market, much as we are now familiar with Grade A meats or restaurants.2 These early inventions, combined with the development of the written examination, were the key ingredients to establishing the grading system that is so central to contemporary schooling.

These early systems of grading were designed for pedagogical purposes. Grades could provide feedback that could be easily understood by students and parents. Such feedback could be provided with greater regularity than the less frequent and more time consuming oral debates that had been the primary evaluation system prior to this innovation. The great educational reformer Horace Mann believed that periodic written communications – much like the report card – could reduce the competitive nature of oral debate and prioritize student learning.3 As a technology to improve learning, grades, if done well, can provide immediate and specific feedback regarding student learning and skill development. Considered as an aspect of the relationship among student, teacher, and parent, grades and marks are a useful technology with the capacity to strengthen the learning process for students. However, while school is a central place of learning, schooling systems are extremely complex and have an energy and needs of their own. Grades can serve the needs of the learner, and grades can serve the needs of the schooling system. While those needs may overlap, more often they diverge.

Mass compulsory schooling in the United States emerged from a series of basic commitments of the fledgling democracy. The vision for the country was rooted in a desire for democratic equality, social efficiency (for citizens to have the necessary skills for the country to function), and the possibility for social mobility.4 Over the course of the nineteenth century, schooling became a central path to achieving these goals. As a result, the numbers of students and schools increased significantly, as did the number of years that students attended school. As students spent more years in school, applied to attend new schools, and began to display their academic achievements as employment credentials, schools needed an easy means to communicate with each other and with others about individual students. “Grading systems that had traditionally tended towards the local and the idiosyncratic, and which were designed for internal communication among teachers and families attached to a given school, became forms of external communication and organization as well.”5

While grades as feedback and grades as a mode of networked communication are not inherently contradictory, the competing needs did create a tension regarding the primary purpose of grades and how they were to be used. Grades for internal communication serve as a pedagogical tool, providing feedback to students and parents about each student’s successes and achievements as well as areas in need of improvement. Grades as a mode of communication between schools created a “grammar of schooling” that could be easily interpreted by people on different sides of the country – people who did not know anything about each other or the student in question. Used in this way, grades became a mechanism for creating a national education system and a means of sorting students. Simple to use, grades, which were conceived to help guide students in their learning, quickly became a useful impersonal network and systems-builder. This basic tension has been present in our grading systems for two centuries.

Our Grading/Schooling Ecosystem

In today’s world, grades, schooling, teachers, students, parents, and colleges are intertwined in a powerful ecosystem with synergistic forces that are difficult to escape. Still, analyzing and articulating the forces that comprise the system and highlighting each constituent’s contribution to it can perhaps provide hitherto unidentified opportunities for individual and collective agency and decision making as participants in the ecosystem. I will draw on David Labaree’s market-based analysis of grades and credentials to describe these systems.6

National schooling systems can be conceived as a public good or a private good. As a public good, schooling aims to generate an educated citizenry with equal opportunity for material success and meaningful cultural engagement. The American public school system was originally conceived as a public good, similar to health care, transportation systems, and public safety. A thriving society imbued with shared values invests in public goods for the benefit of all. On the other hand, education conceived as a private good is a means for individuals to get ahead in accordance with their individual goals and desires. In such a system, one may choose to personally invest in one’s education or not to the degree that it seems beneficial. As Labaree describes, these conceptions have long been in tension in the American system, with reformers promoting education as a public good and consumers using education as a means to get ahead. Seen in this way, students and their parents are consumers who see education as the means for potential social mobility, to provide for one’s family, and to attain wealth or prestige. Schooling is thus a system of credentialing that allows a student to progress through its levels to achieve other goals; learning is important but secondary to achieving the credential. Grades, then, become a commodity to be traded for advancement. Ironically, democratic education that exists ostensibly to provide equal access to learning for all becomes a credentialing system that results in the commodification of grades and of education itself. The consumptive orientation of late capitalism penetrates deeply and shapes the educational system.

While the credentialing system does not contradict or cancel the natural curiosity of students nor their desire to learn – nor does it negate their parents’ desire for their children to receive a high quality education – nonetheless, the commodified, consumerist aspect of grades, diplomas, and admissions has gained primacy. As educators, we would like schooling to be about learning. In many ways, it still is. Yet, in an ultimate sense, for American students, schooling comes down to the grades.

Such is the impact of grades on the educational system when considered from the perspective of the educational market. This commodified dynamic lies at the core of the system, significantly shaping students’ experiences and determining their educational goals and their parents’ hopes for them as well. But to work as a system, others must participate. High schools (administrators and teachers), colleges, and the College Board are central to making this synergistic system work as cohesively as it does. Furthermore, these forces have penetrated so deeply that student self-image and social standing (or cultural capital, as Bourdieu would say)7 are often all too dependent on their grades, and this, too, is an element of the ecosystem.

From the marketing perspective, grades have become commodified. But from the political perspective, and in an attempt to combat social hierarchies, schools were seen as offering equal opportunity for all students. Through schooling, society can leave aristocracy behind. In its place, we could develop a meritocracy which, until recently, was understood as a societal good, a way to combat inequality.8 To earn something based on merit implies that it is not based on class, race, or family connection. Grades could be the great equalizer. Grades are objective, reflecting how well one has learned and how much one has achieved. A transcript describes a reality separated from the various social forces at play.

This idea has come under attack in recent years: meritocracy should combat inequality but it might, in fact, feed inequality.9 In addition, in day-to-day experience, the meritocratic ideal shapes the anxious student experience that I seek to describe. Meritocracy requires an alleged objectivity, which then quantifies the students themselves and increases competition between them by using available data like grades, transcripts, test scores, and lists of clubs and activities. These sorting mechanisms objectify students, requiring increasing perfection from them and affecting student curricular and co-curricular choices, increasing the stakes of every grade a student earns and each club a student joins. I want to highlight the way that the consumerist disposition on the student side and the meritocratic, sorting disposition of higher education work together to create an ever-intensifying cycle: because meritocracy is rooted in competition, the person in first place wins. Since we can always work harder and try to do better, the standards and the intensity will increase so long as we strive to be in the highest percentile or gain admission to the most prestigious institution. But at what cost?

As teachers and administrators, we wring our hands. Why does it have to be this way? We lament that we are not in a position to effect change. For us, school is about teaching and learning. The system is forcing our hand and shifting our priorities. A few years back when I expressed this sentiment, a colleague demurred. You run a school. Thousands of students and parents have come through your building. You have agency; you have a role to play. Upon reflection – and without seeing a way out – I did begin to observe the ways that we, as educators, are complicit in this commodified, meritocratic, tension-filled cycle. Our involvement relates to how we use our disciplinary power.

Grading and Disciplinary Power

There is another fruitful path to explore. “Grading for learning” also came into contact with a system of “disciplinary power” that was deployed starting from the Early Modern period until today. Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish traces the shift from the sovereign power of the king in medieval times and antiquity to a disciplinary power that is “capillary” and “is everywhere.” Modern society is shaped through expectations and normalizing behaviors that are communicated through modern institutions such as the military, the hospital, the factory, and the school. In all of these spaces, power is not oppressive; it is constitutive. According to Foucault, the modern subject is formed through hierarchical observation and normalizing judgment. These elements come together in the examination.

The examination combines the techniques of an observing hierarchy with a normalizing judgment…It establishes over individuals a visibility through which one differentiates them and judges them…The superimposition of the power relations and knowledge relations assumes in the examination all its visible brilliance…For in this slender technique are to be found a whole domain of knowledge, a whole type of power.10

Foucault refers here to the medical or psychiatric exam as much as to the academic exam. He sees in all of these a similar technology, a mechanism through which to set standards, observe, and grade in accordance with an established norm. For Foucault, the end of monarchy and the apparent freedom from the physical power of the sovereign was replaced by the more invisible but ever-present observing eye. As education historian David Hogan states, “individual subjects become the bearers of their own surveillance by internalizing a sense of perpetual visibility.”11

From this perspective, teachers are the observers in a hierarchical relationship where students are constantly evaluated against a norm that forces them to self-discipline in order to earn the approval of those who grade them. While the established norms are by no means haphazard, they do place students in the position of being constantly observed in a manner that, while not physically oppressive, makes every action of potential consequence, occuring before the eyes of “the grader,” the person who will ultimately rank and convey status upon the student, whether by letter or number.

Foucault’s interest is in the constitutive systems of power and not in the agency of any particular individual (in fact, he is critiqued for insufficient attention to the agency and intentionality of individuals in effecting change), but as teachers we must acknowledge the enormous power that we yield in the school setting in general and in the classroom setting in particular. We use this power intentionally to maintain decorum, and control student behavior. Every time a teacher says, “remember that in order to be successful in college, you need to…”, the teacher is wielding this disciplinary power. That sentence uses the power of grading as leverage to gain compliance. Furthermore, through such talk, we are also imposing ideas about identity and ways of being. The teacher is saying, “it is important to do well in school. Getting good grades is what matters. Following my instructions will help you get there.” I am not saying that it is wrong for teachers to say this. But it is most certainly complicated and consequential.

Grading and measuring are pervasive in our school system. We might have good reasons for grading tests, papers, homeworks, attendance, timeliness, class participation, and preparation for class. Yet Foucault and Hogan would say that the constant grading has enormous constitutive consequences, impacting our students’ identities and senses of self-worth. It shapes students’ souls, their way of being in the world. Without intention, school administrators and teachers contribute to maintaining the pressurized, grade-oriented ecosystem by using grades as leverage for compliance. There might be no other way; it might be what is best for students in order to achieve in the social framework that we inhabit. However, we need, at least, to identify it so that we can consider the tradeoffs carefully.

While we often talk about the importance of good grades for getting into elite colleges, grades are a standard bearer for most Modern Orthodox students’ sense of personal success and failure, whether or not they hope to attend an elite college. Good grades are a symbol for being a successful young adult. Therefore, while, from a market perspective, grades serve as currency to achieve the next step on the ladder, grades serve as social currency as well. In our society, good grades signify a great deal about a young adult; good grades even result in better car insurance rates. Students who do not earn good grades need to figure out a different way to earn the respect of their peers and the adults around them. It is extremely difficult for a student and their parents to say, “Sara is just not cut out for school. She would benefit from something other than attending classes all day for 12, 16 or 20 years.” While it is possible to do so, it is difficult to make that decision because of the social currency of carrying good grades.

Grades as Leverage for Learning

We have focused on some of the grimmer aspects of our grading systems, But we must take note of the positive impact that these forces have on student learning. From my own decades of experience as a high school principal, I believe that the importance we assign to grades helps create a serious culture of learning in school. In conversation with fellow principals, I often have the opportunity to compare high school experiences of students in independent and public high schools or American and Israeli high schools. Although not data driven, my experience is that when grades are important, learning is taken more seriously. A qualitative experiment in my class bore this out.

In 2013, our faculty did an experiment called the Lishma Project. In a yeshiva high school setting, students often ask their teachers, “why can’t we just learn lishma,” calling on their teachers to give teeth to a value that we preach often: the importance of learning for learning’s sake. In a Jewish school, we teach that learning is an intrinsic good and not only a means to an end. We should learn in our “spare time.” Learning does not take place only in school or only in order to earn grades. And yet, in practice, almost all school learning is tested and graded. The Lishma Project was a response to that challenge. Each faculty member committed to teaching one unit during that year without requiring any homework or giving any assessments on the unit. Faculty shared strong opinions both in favor of and in opposition to the project, but we all implemented the experiment. My personal experience with that project has remained with me and, based on the qualitative experience of that single case, profoundly shaped my views on grading.

In my tenth grade Talmud class, I give oral bechinot. I sit with each student individually and listen to them read each sugya that we learn. I do so because I seek to emphasize the importance of reading skills and the ability to explain texts and ideas in spoken Hebrew. The final is cumulative. Each student must select 6 of the 8 sugyot that we learned during the year, and we learn those texts together, also in a one-on-one setting. As I gave the final exams during the year of our Lishma project, I began to notice that none of the students had selected the unit that we had learned lishma. After 7 or 8 tests, I began to ask each student why they did not select that sugya. The response in each instance was the same: “I did not review that Gemara for a test, so I don’t know it as well. Therefore, I did not select it for the final.”

I was very moved by that experience. On the one hand, while teaching and learning that sugya together in class, I saw no difference between that unit and all the others. Students were equally engaged and participated in class discussion as usual; I felt no lessening of attention or interest. And yet, they did not internalize what they had learned in the same way. When students practice reading a Gemara many times, they can recite segments from memory and refer back to the text when appropriate. All that was lacking in our lishma unit.

In my own class, assessments provided reason for students to review. Knowing that they will be evaluated, students learn and practice with greater care. One could argue that the tradeoff is worth it. Perhaps a little less clarity and a lot less pressure is a better result; perhaps not. But identifying the tradeoffs can help us make thoughtful decisions that align our practice and our goals. For example, many have suggested that yeshiva high schools grade general studies classes but not grade Limudei Kodesh. The implicit concept in this position is that learning lishma is optimal, and grades replace that ideal by making learning the means to a greater end. Therefore, while we might need to grade general studies, we should keep the purity of our Limudei Kodesh classes and not grade those classes. The counterargument goes like this: students have been trained to learn in a graded system. Grading something means that “it counts.” Classes that are not graded are less serious. A colleague suggested that we need to lean into the power of grades in order to ensure that students take all of their classes seriously. In fact, she claimed, we should give projects and homework in similar proportions in our Limudei Kodesh classes precisely to express that we take the knowledge and skills seriously. That is accepting and working within the reality of our system.

The Lishma Project exposed a meaningful aspect of individual student learning. But grades might have a broader cultural effect as well. Again drawing on anecdotal experience, Israeli educators who have come to teach in our American yeshiva system have, over many years, noted that our students are serious about learning. They are responsible, care about their classes, and work hard. The teachers note the difference between students in the American high school system and their Israeli counterparts. The subsequent analysis of the educators always arrives at the same place. Israeli students are thinking about their futures in the IDF. That is the next stage in their lives. Their high school grades are of relatively little consequence. For their American high school counterparts, everything centers on grades. They are thinking about college and, for that, the grades matter. Considered from this vantage point, grades do indeed create pressure and are used for leverage, but the leverage is well placed. Students learn what is expected of them based on where the pressure is placed. As Foucault described in great detail, power is necessary to establish the “means of correct training.”

The exercise of discipline presupposes a mechanism that coerces by means of observation; an apparatus in which the techniques that make it possible to see induce effects of power, and in which, conversely, the means of coercion make those on whom they are applied clearly visible.12

Foucault describes “normalizing power” through discipline as the mechanism that drives systems as diverse as the military, hospitals, prisons, mental health, and schools. All of these institutions use hierarchical observation, normalizing judgment, and the examination as elements of shaping a system that disciplines the subjects in that system. We might shudder at the association of schools with prisons and hospitals. Still, teachers do give examinations, assessments, tests, quizzes – whatever term we employ – in order to observe, evaluate and classify students. Teachers employ the mechanism, and students learn because they have accepted – willfully or otherwise – that they are part of this system. In our schools, students receive excellent education perhaps precisely because of this system that has been built over the past two centuries. In making change without careful consideration of the tradeoffs involved, we risk weakening an educational system that is serving our students very well in providing them with rigorous educational experiences that allow them to learn, grow and develop skills, capacities, and interests that they might otherwise not realize that they have.

Considering the Options

Harvard, Brown, Yale, NYU, and many other elite colleges received record numbers of applications this year.13 Applications have been increasing annually over the recent years, and the percentage of students accepted has been steadily dropping for quite a while. In 2022, Harvard, Brown and Yale accepted 3.2%, 5% and 4.5% of students that applied.14 In 1995, the University of Chicago accepted 72% of students who applied. In 2022, they accepted 7.2%! The world of college admissions has changed dramatically even in the relatively short life of SAR High School. The process has intensified to unhealthy proportions. While none of us intends to do so, our participation in the networked grading ecosystem is harming our children. Their anxiety levels are rising, they are required to strive for perfection, there is no room for error, and they are giving all of their energy toward a goal that they do not fully understand. In the process, they lose the opportunity to healthily learn from making mistakes, from trying and failing – or even trying and performing less than perfectly.

Our school is not able to change a deeply entrenched and entangled system. I do not have a solution to the problem; there’s no silver bullet. However, as a school, and as individual families with agency, small decisions can make a difference and help reshape our school culture. Modest change can make a difference in the life of a student, their sense of self worth, their experience of school, and their relationship with their parents. I do not have revolutionary solutions. But evolutionary strategies can help shift the culture in a meaningful way.

In a short monograph, Exit, Voice and Loyalty, the economist Albert O. Hirschman describes the two basic human responses when people see that a service, product, community, or even nation is declining or not benefiting the consumer as it once did. They can choose to exit the system and move on to other products or options, or they can use their voice to express their disapproval with the goal of improving the product or system. Loyalty to the product or system determines which option the individual will choose. Greater loyalty to the system will bring a desire for improvement, a drive to effect change. Less loyalty will more likely result in exiting the system. A similar self-evaluation is in order regarding our grading systems, for individual students and families and for us as a school. Some feel that the overall system provides more good than bad. For others, the system is corrosive and needs more dramatic changes. One might choose to work within the system, and work to provide a better balance of values. One can instead choose to exit a system that is not working for them.

One option is to lean in. We live in a world of grades and tests. There is no way to escape the deeply networked system. Our students take school seriously because of it, and they learn and achieve in impressive ways. While we might critique aspects of the system, we should appreciate the high levels of learning that have been achieved.

Even so, we do have agency regarding what we grade and why. Rather than grading test scores, we might grade habits of mind. We might put less emphasis on answers that evaluate skills and knowledge and shift our emphasis to character traits: engagement, participation, listening, punctuality and many others traits.

Some people might choose, at least to a degree, to exit the most competitive aspects of the system. Our community has its own institutions, colleges that feel a sense of connection and loyalty to our community’s children. We often take that loyalty for granted; or worse, we interpret institutional loyalty as a sign of lower standards. That is an unfortunate interpretation. When families decide and students know that they will be attending Yeshiva University or Touro University, the pressure of grades is reduced. That release of pressure can free one’s mind to learn, explore, and grow in high school. While high grades and scores are necessary to earn scholarships or admission to certain select programs, it is possible to take the edge off of the high school experience because the student knows that they have a seat in a strong college program. The same can be said for attending college in Israel. For this reason, among others, attending college in Israel should become more of an option for our graduates.

It is important to gather and provide our students and parents with useful data (quantitative or qualitative) about the impact of the commodities goal on our broader school mission. This should happen early on in one’s high school experience. Parents and students must understand the impact of meritocracy on our life experience and the statistical trends regarding college admissions. We should share stories of successful graduates who took different paths to success. We need to do more to help ourselves and our students imagine different ways of “doing school.”

We might create megamot – majors or tracks – for students who have an interest and passion that is not rooted in best grades for the most prestigious college. For example, serious Torah learners and serious artists might not be invested in the path that is necessary for “building a transcript” for college and might welcome a different path. While we will not return to the vocational training programs of the last century, we should consider offering a wider range of academic programming.

As administrators, we must implement a cultural shift that will rebalance our institutional, familial, and student priorities around the goals of high school. Currently, it is widely accepted as common sense that the student’s most important responsibility is to earn the highest grades in the most challenging courses. Even those who wish it were different are pulled into that mindset. But we can take steps to improve the balance and begin to shift the culture.

Most basically, teachers should never use college as a motivator for students to work hard and earn grades. We need our teaching to be excellent enough to draw students into the learning without referencing preparation for college. The high school experience should not be thought of or spoken about as college preparatory work.

We must change the discourse around grades and transcripts in our school. We must find opportunities to communicate throughout the college process that students and families have agency and the ability to think about their futures in terms that are less transcript focused. As part of the college process, parents and students should have an opportunity to consider what type of college process and high school experience they seek. We should design a self-reflection survey and questionnaire for parents and students to help them think about personal and educational goals and aspirations – and what drives their course selection. This should be used as a basis for deliberation and discussion early on (perhaps tenth grade) about what is most important to them in their high school education. Quite often, students think that grades are most important to their parents and might be surprised to see that their parents articulate different hopes and goals for their children. We need to invest more time and create a more reflective process for families to articulate what they hope to gain from the high school experience.

We should consider ways to separate the networked grades from the feedback grades. While this would require much thought and planning – and would undoubtedly generate unintended consequences – disentangling the feedback system from the networked system in certain spaces of the school can provide a protected space to provide direct feedback without the concern of long-term effects on the student hovering over the exchange. For example (in an area where we currently do not grade at all) should students receive grades for tefillah? Most teachers, students, and parents think not. However, most people also think that receiving feedback on how davening is going for the student is a good thing. The tefillah example shows how the networked system of grades creates an obstacle to providing feedback to students and parents regarding one of our most important goals. Perhaps we cannot escape the system, but we can control what values we emphasize and make necessary changes to provide feedback that is separate from the networked system.

Cultural change is slow and challenging. It often occurs through broad social forces that extend beyond what each of us is able to control. Still, conscious awareness and clearer understanding of the world we inhabit combined with intentional collective action can make a difference in the lived experiences of our students and children.

Footnotes

- This paper was written towards the end of 2022 as part of a Machon Siach grading cohort project. Since then, the climate on college campuses around the world has changed dramatically for Jewish students, particularly after October 7, 2023. The concerns of antisemitism, unenforced campus rules, and instability have raised severe questions and challenges for us to consider. I acknowledge those questions and challenges. As they are not the focus of this paper, I will not address them here.

- Hoskin, Keith W. and Macve, Richard H., Accounting and the Examination: A Genealogy of Disciplinary Power, Accounting Organizations and Society, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 105-136, 1986.

- Hutt, Ethan and Schneider, Jack, A History of the A-F Marking Scheme; Journal of Curriculum Studies, 2013, page 6.

- Labaree, David, How to Succeed in School Without Really Learning, Yale University Press (New Haven:1997), pp. 19-36.

- Hutt and Schneider, p. 2

- David Labaree How to Succeed in School Without Really Learning; (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1997), chapter 1; idem, Someone Has to Fail: The Zero-Sum Game of Public Schooling; (Harvard University Press, 2012).

- Bourdieu, Pierre, The Forms of Capital, Richardson, J., Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1986), pp. 241–58.

- The history of the term is different than commonly understood. In 1958, the British sociologist Michael D. Young published The Rise of the Meritocracy, a dystopian work of fiction describing a society divided between the merit-holding privileged elite and those who did not achieve such success and remained the underprivileged class. When Young coined the term, he intended it as a satire of the way education was being practiced at the time, creating a successfully schooled elite class and an underclass which was composed of students who failed in the competitive school market. The term has not been used with the meaning that Young intended. Instead, it refers to, as popularly perceived, a proper mechanism for combating inequality.

- Markovits, Daniel, The Meritocracy Trap, (Penguin Books: New York, 2019); Sandel, Michael, The Tyranny of Merit: What Became of the Common Good? (Farrar, Straus,and Giroux: New York, 2020)

- Foucault, Michel, Discipline and Punish, (Vintage Books: New York, 1995), p. 170.

- Hogan, David, Examinations, Merits and Morals: The Market Revolution and Disciplinary Power in Philadelphia’s Public Schools, 1838-1868, HSEIRHE, 4, 1 (1992) pp. 31-34.

- Foucault, pp. 170-171.

- These are 2022 data. The ecosystem has since been further destabilized by the increasingly divisive culture wars and the rise of uncontrolled demonstrations and antisemitism since October 7.

- Belkin, Douglas, To Get Into the Ivy League, Extraordinary Isn’t Enough These Days. Wall St. Journal, April 21, 2022.