The Sound of Silence: Mishnah Berakhot 2:3

Introduction

The primary focus of the second chapter of Masekhet Berakhot is proper and improper ways to recite Keriat Shema, what is included in its corpus, the level of concentration necessary to fulfill the obligation, and how it should technically be articulated. The third Mishnah in the chapter records a series of halakhot related to the proper recitation of the text of the Shema:

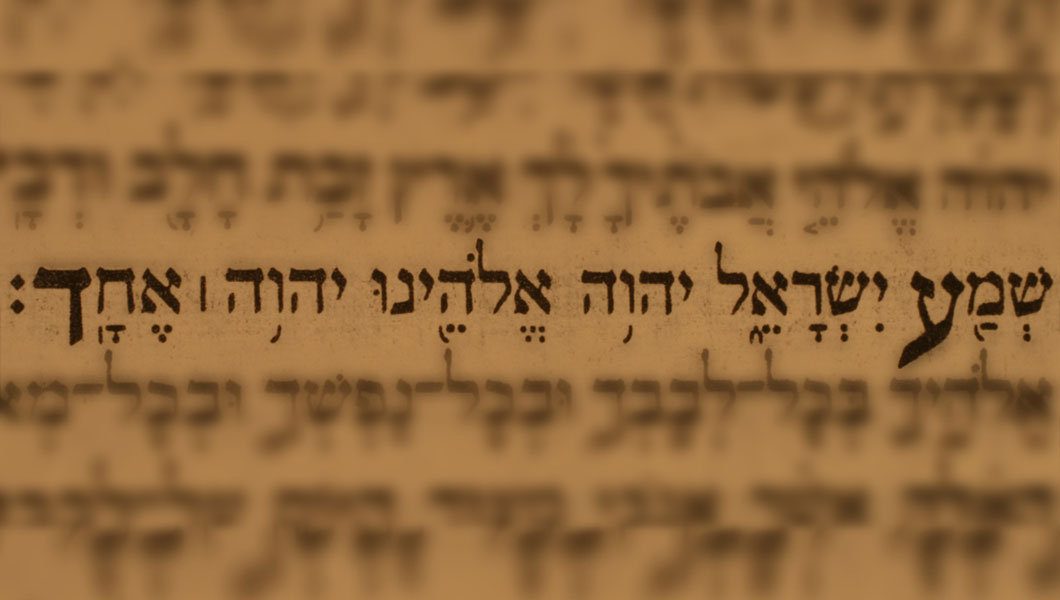

הקורא את שמע ולא השמיע לאוזנו יצא; רבי יוסי אומר לא יצא. קרא ולא דיקדק באותותיה רבי יוסי אומר יצא; רבי יהודה אומר לא יצא. הקורא למפרע לא יצא. קרא וטעה חוזר למקום שטעה.

One who recites Shema but it was not audible to his own ear, fulfilled his obligation. Rabbi Yosi says: He did not fulfill his obligation. One who recited Shema but was not precise in his enunciation of its letters, Rabbi Yosi says: He fulfilled his obligation. Rabbi Yehuda says: He did not fulfill his obligation. One who recited Shema out of order, did not fulfill his obligation. One who recited and erred, should return to the place that he erred.

The Bavli (Berakhot 15a) proceeds to discuss the source of the view of the Tanna Kama and Rabbi Yosi regarding hearing one’s own recitation of the Shema.

מאי טעמא דרבי יוסי? משום דכתיב “שמע”: השמע לאזנך מה שאתה מוציא מפיך ; ותנא קמא סבר “שמע” – בכל לשון שאתה שומע ; ורבי יוסי? תרתי שמע מינה.

What is the reason behind Rabbi Yosi’s opinion? Because it is written “Shema,” which implies that your ears should hear what your mouth says. And the Tanna Kama holds that the implication of “Shema” is that it can be recited in any language you hear [i.e. understand]. And Rabbi Yosi holds that both laws are learnt from “Shema.”

It then goes on to discuss whether the Tanna Kama of the first case is to be interpreted only as a post facto concession, bedieved, or even as a lekhatchila ruling that allows for this to be done as standard practice. The Bavli examines this question by comparing similar rulings relating to both people who are deaf and those who can hear but choose not to express the blessing verbally, regarding the laws of blessings, Birkat Hamazon, and, later in the sugya, Megillah reading.

The back and forth of this section of the sugya is very technical and constitutes what is popularly known in the yeshiva world as cheshbon, i.e. formally aligning a view in one area with the view in another area to see if the principles and halakhot align. Because the text and its underlying issues are so technical, many teachers, including, for many years, myself, skip this entire Mishnah and sugya and go immediately to the next Mishnah and its Gemara.

As an alternative, some teachers immediately turn to the Gemara’s much shorter discussions of the last three halakhot of the Mishnah on the bottom of the next page of the Gemara (Berakhot 15b).

אמר רב יוסף: מחלוקת בקרית שמע אבל בשאר מצות – דברי הכל לא יצא דכתיב (דברים כז ט) [וידבר משה והכהנים הלוים אל כל ישראל לאמר] הסכת ושמע ישראל [היום הזה נהיית לעם לה’ אלקיך]! מיתיבי: לא יברך אדם ברכת המזון בלבו ואם בירך – יצא!? אלא אי אתמר – הכי אתמר: אמר רב יוסף: מחלוקת בקרית שמע דכתיב “שמע ישראל,” אבל בשאר מצות – דברי הכל יצא.

Rabbi Yosef said: The dispute is in regard to Keriat Shema, but in all other cases there is agreement that one does not fulfill his obligation. As it is written, “Pay attention and hear, Israel” (Devarim 27:9). The Gemara objects based on a bereita. One may not recite Birkat Hamazon in his heart [i.e. inaudibly], but if he did recite it so, he has fulfilled his obligation. If Rabbi Yosef’s statement was said, he must have said that there is a dispute in regard to Keriat Shema, as it is written “Hear, Israel.” But in regard to any other mitzva, everyone agrees that you have fulfilled your obligation.

R. Yitzhak Alfasi (Rif), in his halakhot, indeed condenses the nearly full daf’s worth of discussion of the Mishnah’s first halakha into barely two lines of text:

אמר רב יוסף מחלוקת בקריאת שמע אבל בשאר מצוות דברי הכל יצא דתניא לא יברך אדם

ברכת המזון בלבו ואם ברך יצא.

Rav Yosef says: There is an argument regarding the recitation of Shema, but by all other mitzvot, everyone agrees you have fulfilled your obligation. As it is taught, a person should not recite Birkat Hamazon to himself, but if he did, he has fulfilled his obligation.

This is a fully valid pedagogical approach to teaching the sugya that avoids getting lost in the thicket of the Talmudic back-and-forth that could be challenging for many students. It also achieves the pedagogical goal of highlighting and educating students on what the Rif set out to do in his corpus; his relationship to the text of the Talmud here is a fitting example of his methodology.

This paper offers an alternative to these approaches and suggests a more focused effort in presenting the first halakha in the Mishnah to high school students. It argues that one can teach this Mishnah and sugya with its important halakhot that touch on key issues of the nature of Keriat Shema. This approach may be especially appropriate in an advanced or accelerated class, which can be challenged to handle this complex material. It can also be presented as a deeper dive into the sugya after first learning the Rif’s condensed model.

The first pedagogical move in teaching this Mishnah is to redirect the discussion to the parallel section in the Tosefta (2:3-4). Next, students should turn their attention to the short Mishnah and sugya in Berakhot 20b, which will serve as the basis for further analysis.

The teacher, after analyzing the Mishnah and the comparison to the Tosefta and the Mishnah on daf 20b, can then selectively choose to read the first part of the shakla vetarya until the beraita regarding Birkat Hamazon. In this way, the student experiences the back and forth of the sugya without getting bogged down in the repetition of the cheshbon on 15b nor the Gemara’s excursion into the world of megillah reading, the aside about a katan, or the obligation of chinukh, which is mentioned in passing and taken up by Tosafot and many Rishonim.

A. Comparison of Mishnah Berakhot 2:3 and 3:4 to Tosefta Berakhot 2:3-4

Chapter 2 of Tosefta Berakhot focuses on the proper way to recite Keriat Shema. It begins with the requirement to mention the Exodus in Keriat Shema (a law mentioned at the end of chapter 1 in the Mishnah) and then proceeds to require intention in reading Keriat Shema in parallel to the first Mishnah in chapter 2. The Tosefta then records:

2:3 הקורא את שמע למפרע לא יצא וכן בהלל וכן בתפלה וכן במגלה.

2:4 הקורא את שמע וטעה והשמיט בה פסוק אחד לא יחזור ויקרא את הפסוק בפני עצמו אלא מתחיל באותו פסוק וגומר עד סוף וכן בהלל וכן במגלה וכן בתפלה

2:3 One who reads the Shema out of order has not fulfilled his obligation. The same applies for Hallel, Tefillah, and Megillah.

2:4 One who reads Shema and made a mistake and skipped one verse, should not begin to read that verse by itself, but rather should go back to that verse and complete [the Shema, from that point on] until the end. The same applies for Hallel, Tefillah, and Megillah

It is striking to note that the Tosefta does not mention the law of reading Keriat Shema without pronouncing the words accurately nor, for our purposes here, the law of not verbally expressing Keriat Shema in such a way that it can be heard (hishmiah le’ozno). Students can easily note this glaring omission when compared with the Mishnah. It immediately raises the question of why the Tosefta differs so plainly from the Mishnah.1 In this short paper I am not exploring the exact relationship between the Mishnah and Tosefta, which came first, and if one assumes the existence of the other. Whatever view one ultimately takes on these scholarly issues, I am using the contrast between the Mishnah and Tosefta’s formulations as a springboard to discuss potential contrasting views about the nature of Keriat Shema. Ascertaining the truth value of the ideas and paradigms raised that push students to think in varied conceptual terms about the nature of Keriat Shema from a careful reading of these texts is an important skill to learn and a legitimate goal, though it may not be the only way to unpack the sugya.

The picture is further complicated by the fact that the Tosefta (2:13) does mention the concept of hishmiah le’ozno much later in the chapter during its discussion of the ba’al keri:

בעל קרי שאין לו מים לטבול הרי זה קורא את שמע ואינו משמיע לאזנו ואינו מברך לפניה ולא לאחריה דברי רבי מאיר. וחכ”א קורא את שמע ומשמיע לאזנו ומברך לפניה ולאחריה. אמר רבי מאיר פעם אחת היינו יושבין לפני ר’ עקיבה בבית המדרש והיינו קורין את שמע ולא היינו משמיעים לאזנינו מפני קסדור אחד שהיה עומד על הפתח. אמר לו אין שעת הסכנה ראיה.

A man who had a seminal emission who does not have water to dip in may read the Shema, but he may not [read it loud enough to] hear with his own ear, and he does not say the blessings before and after it. These are the words of Rabbi Meir. And the Sages say he may read the Shema and he may [read it loud enough to] hear with his own ear, and he says the blessings before it and after it. Rebbi Meir said, “One time we were sitting in the study hall before Rabbi Akiva and we were reading the Shema, but we were not saying it loud enough to be able to hear ourselves, because of one inquisitor who was standing by the door.” They (the Sages) said to him, “The time of danger is not proof.”

The Mishnah in Berakhot (3:4) also discusses ba’al keri towards the close of the third chapter; however, it does not use the term hishmiah le’ozno as part of its presentation:

בעל קרי מהרהר בלבו ואינו מברך לא לפניה ולא לאחריה

One who is impure from a seminal emission contemplates [Shema] in his heart, but does not say the blessings before and after.

Here, strikingly, the Mishnah introduces a new concept, hirhur belev, a term missing from any discussion in the Tosefta.2 It is interesting to note that Penei Yehoshua on Mishnah 2:3 asks why the sugya did not bring up the Gemara on 20b regarding hirhur belev of a ba’al keri, and makes the difficult suggestion that the sugya on 20b is only based on view of Rabbi Yosi who permits hishmiah le’ozno and not according to all views in our Mishnah. R. Saul Liberman in Tosefta Kifshuta also asserts (without citing Penei Yehoshua) that Mishnah 2:3 is according to the view on 15a that hishmiah le’ozno is not valid (i.e. Rabbi Yosi’s view). As such, the plain sense of Mishnah 3:4 is that Keriat Shema can be recited regularly and hirhur belev relates only to the blessings of Keriat Shema, as is clear in the Yerushalmi on the Mishnah 3:4 (which differs from the Bavli’s reading). The Mishnah thus cannot suggest hismiah le’ozno as an option for the ba’al keri. This term refers to thinking about the words one is reading without any verbal articulation. It is an expression of the sound of silence. Interestingly, a computer search3 Conducted via the Bar Ilan Responsa database. of the entire Tosefta does not find any reference to the concept (nor even the terminology) of hirhur as a possibility in any classic ritual context at all, neither in the world of berakhot nor Megillah nor Keriat Shema. The term is used once in Mikva’ot chapter 6 in reference to one who has a dream of having sexual relations (המהרהר בלילה ומצא אברו חם) and in one other context regarding technical laws of tuma and tahara in Tosefta Zavim.

The lack of any mention of the term hirhur in the Tosefta in the context of blessings and recitations may indicate that this was not a legitimate ritual option in the eyes of the Tosefta. In its conception of reading a ritual text or making a blessing, words must be enunciated, and sight reading or simply thinking about the words in your heart is not a live option.

Differing Conceptions of Keriat Shema

In resolving these disparities between the Mishnah and Tosefta for students, one can suggest that each source understands the mitzvah of Keriat Shema differently. A central question that emerges in many sugyot regarding Keriat Shema is whether to view it primarily as a form of minimal daily Talmud Torah that is prescribed by the halakha (either on a biblical or rabbinic level), or to view it as an entirely separate mitzvah that involves affirming core principles of faith and God’s kingship.

This broad debate emerges throughout the study of the topic of Keriat Shema.4 See for example Gigi, Baruch. Review of Keriat Shema (VI): The Torah Study Aspect of Keriat Shema. (Yeshivat Har Etzion: 2015)https://www.etzion.org.il/en/philosophy/issues-jewish-thought/topical-issues-thought/keriat-shema-vi-torah-study-aspect-keriat. An example of this basic debate emerges in the discussion as to whether those who study Torah all day long are exempt from reciting Keriat Shema. Shabbat 1:2 explicitly states: “מפסיקין לקריאת שמע ואין מפסיקין לתפילה”. Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, cited in the Yerushalmi on that mishna, argues that those who engage in full-time Torah study are also exempt from recitation of the Shema. The explanation given is that “זה שינון וזה שינון”, Keriat Shema is simply another form of Talmud Torah and thus one can continue there current study.

This rationale may also be at the heart of the simple reading of Berakhot 2:1 which states, “היה קורא בתורה והגיע זמן קריאת שמע אם כיוון לבו יצא.” This situates the question in the context of someone learning Torah who reaches the portion of Keriat Shema in Devarim 6. The question arises: does the individual need to have special intent to transform this act of study into a fulfillment of Keriat Shema, or is its study alone enough, as with any other portion of Torah?5 For more elaboration on this entire question see Shirei HaRav al Inyanei Tefillah veKeriat Shema, ed. R. Menachem Genack (New York, 2010), pp. 69-74 [Hebrew].

If this debate lies at the core of the discussion, a teacher can raise the possibility in class that the Tosefta viewed Keriat Shema primarily as an act of recitation of a creedal affirmation. It thus required a formal act of keriah of a declarative nature. Thus, it could never entertain a notion of lo hishmiah le’ozno, of not verbally making a statement that could be heard as a live option for the fulfillment of the mitzvah of Keriat Shema in regular circumstances.

The Tosefta (2:4) raises only two possible scenarios: may one read Keriat Shema out of order, and what one should do if they skipped a line of Keriat Shema. In those instances, the person has read the text out loud and recited the words correctly but has garbled the meaning for the outside listener. A recitation has occurred, but it may have been faulty as the flow and meaning of the entire passage has been compromised. In contrast, in the cases of lo hishmiah le’ozno or lo dikdeik be’otioteha (mispronouncing words) one can posit that from a conceptual point no recitation has occurred at all. Recitation of a text by definition means reading it out loud and correctly. At the heart of the Tosefta’s conception of the mitzvah is that reading a text correctly is a declaration of a formal text expressing certain ideas; it is not an act of study or contemplation. In the case of a ba’al keri, the Tosefta does not have the concept of hirhur, as that could never constitute a recitation of Keriat Shema. At most, in extreme circumstances, one might raise the option of verbally enunciating the words without sound as an alternative to reading but not as a formal act of reading. In contrast to this understanding, the Mishnah may be more willing to see Keriat Shema as a fulfillment of a formal act of Talmud Torah, prescribed and delimited by halakha. As such, there exists more room to raise the possibility for students that saying the words of Keriat Shema, even if they are not heard, may be enough to fulfill this level of a Talmud Torah exposition that is at the heart of Keriat Shema.6It is of course possible to suggest that both the Mishnah and Tosefta agree that the underlying obligation is קבלת עול מלכות שמים and the difference is whether קבלת עול מלכות שמים is internal and personal or needs verbal recitation.

In the later sugya of ba’al keri, students can observe that the Mishnah may be willing to go further and articulate that simply reading the words of Keriat Shema to oneself without articulating them is possibly enough, just as thinking and contemplating a passage of Torah is a fulfillment of the mitzvah of Talmud Torah, i.e one does not have to articulate the words.

It is here that the class can enter the world of the Bavli and note that a shift may have occurred in its conception of Keriat Shema that pushed it back towards the view of the Tosefta. The amoraic sugya on Mishnah 3:4 is not content to accept the plain sense of the Mishnah that one is engaging in hirhur as an alternative to keriah. It goes further, i.e. it is not satisfied with seeing hirhur as an act that can only be used in extreme circumstances to fulfill one’s obligation. It introduces the notion of hirhur kedibur dami (thinking is like speaking), trying to push the act of hirhur back into the realm of actual speech and formal expression, even if unarticulated and silent. This move brings us back to the sugya we started with on daf 15a and fits well with the agenda of the Bavli in understanding the Mishnah on daf 15a.

Highlighting this move helps students understand part of the scope of the intellectual project of later sources in Chazal such as the Bavli in confronting, interpreting and understanding the received traditions of earlier sources at their disposal.

The Gemara’s discussion of Mishnah 2:3 begins by suggesting that Rabbi Yosi’s insistence on articulating the words of Keriat Shema in a manner that they can be heard is based on a drasha from the word “Shema.”

מאי טעמא דרבי יוסי? משום דכתיב “שמע”: השמע לאזנך מה שאתה מוציא מפיך.

What is the reason for Rabbi Yosi’s opinion? Because it is written “Shema,” which implies that your ears should hear what your mouth says.

Taking these words at face value, as students often do, shows that this injunction should be understood as a limited rule in the world of Keriat Shema. The sugya, however, expands its reach and compares the ruling to other areas of ritual law including berakhot, Birkat Hamazon, and, later, to the reading of the Megillah. It is clear that the Bavli is attempting to see the rule of hishma’at ha’ozen as part of the very definition of any act of formal speech required by the halakha, as part and parcel of the definition of keria or amira. Keriat Shema thus exists as the prime example of a biblical act of declaration and not merely an elaborate form of Talmud Torah, which becomes a source for all acts of declaration in halakha. This expands student’s understanding of what halakhic recitation is all about and what they are doing when they go through their own halakhic life with its richly choreographed guidance and direction.

Conclusions

In approaching the sugya on daf 15a as outlined in this short paper, a number of pedagogical goals and learning outcomes can be achieved by the student.

1. The student learns to read and organize the Mishnah carefully and contrast it on its own terms to the other primary tannaitic source, the Tosefta.

2. The student learns to appreciate subtle differences between the way the Tosefta and Mishnah organize similar material and the fact that they engaged in conscious choices while presenting that material.

3. Students can come to appreciate and understand the intellectual project of later sources of Chazal, such as the Bavli, and how they shaped, understood, and privileged certain understandings of the primary sources they received by tradition.

4. These differences can often yield significant conceptually different models in understanding the halakha. In our case, the work explores how to view the primary aspect of Keriat Shema: is it a formal act of Talmud Torah, or is it an entirely separate mitzvah focused on creedal affirmation?

5. The student can see greater meaning in learning a complicated sugya that seems to be cheshbon but can, with the right approach, yield insight into how to view the substantive nature of Keriat Shema.

6. The student comes into contact with the project and methodology of the Rif, considering a sugya from a bird’s eye view and then returning to view its basic conclusions.

7. The student learns to reflect on a basic component of daily religious life (recitation of Keriat Shema), its meaning and purpose, especially in the way most yeshiva high schools (and many Modern Orthodox shuls) try to implement it in the tefillah context.

8. In a broader sense, this can lead to a discussion of what human beings and religious individuals aim to do when we express religious ideals and values verbally and how our choices might impact on our inner world.

- 1In this short paper I am not exploring the exact relationship between the Mishnah and Tosefta, which came first, and if one assumes the existence of the other. Whatever view one ultimately takes on these scholarly issues, I am using the contrast between the Mishnah and Tosefta’s formulations as a springboard to discuss potential contrasting views about the nature of Keriat Shema. Ascertaining the truth value of the ideas and paradigms raised that push students to think in varied conceptual terms about the nature of Keriat Shema from a careful reading of these texts is an important skill to learn and a legitimate goal, though it may not be the only way to unpack the sugya.

- 2It is interesting to note that Penei Yehoshua on Mishnah 2:3 asks why the sugya did not bring up the Gemara on 20b regarding hirhur belev of a ba’al keri, and makes the difficult suggestion that the sugya on 20b is only based on view of Rabbi Yosi who permits hishmiah le’ozno and not according to all views in our Mishnah. R. Saul Liberman in Tosefta Kifshuta also asserts (without citing Penei Yehoshua) that Mishnah 2:3 is according to the view on 15a that hishmiah le’ozno is not valid (i.e. Rabbi Yosi’s view). As such, the plain sense of Mishnah 3:4 is that Keriat Shema can be recited regularly and hirhur belev relates only to the blessings of Keriat Shema, as is clear in the Yerushalmi on the Mishnah 3:4 (which differs from the Bavli’s reading). The Mishnah thus cannot suggest hismiah le’ozno as an option for the ba’al keri.

- 3Conducted via the Bar Ilan Responsa database.

- 4See for example Gigi, Baruch. Review of Keriat Shema (VI): The Torah Study Aspect of Keriat Shema. (Yeshivat Har Etzion: 2015)https://www.etzion.org.il/en/philosophy/issues-jewish-thought/topical-issues-thought/keriat-shema-vi-torah-study-aspect-keriat.

- 5For more elaboration on this entire question see Shirei HaRav al Inyanei Tefillah veKeriat Shema, ed. R. Menachem Genack (New York, 2010), pp. 69-74 [Hebrew].

- 6It is of course possible to suggest that both the Mishnah and Tosefta agree that the underlying obligation is קבלת עול מלכות שמים and the difference is whether קבלת עול מלכות שמים is internal and personal or needs verbal recitation.