לא תעמד

Introduction

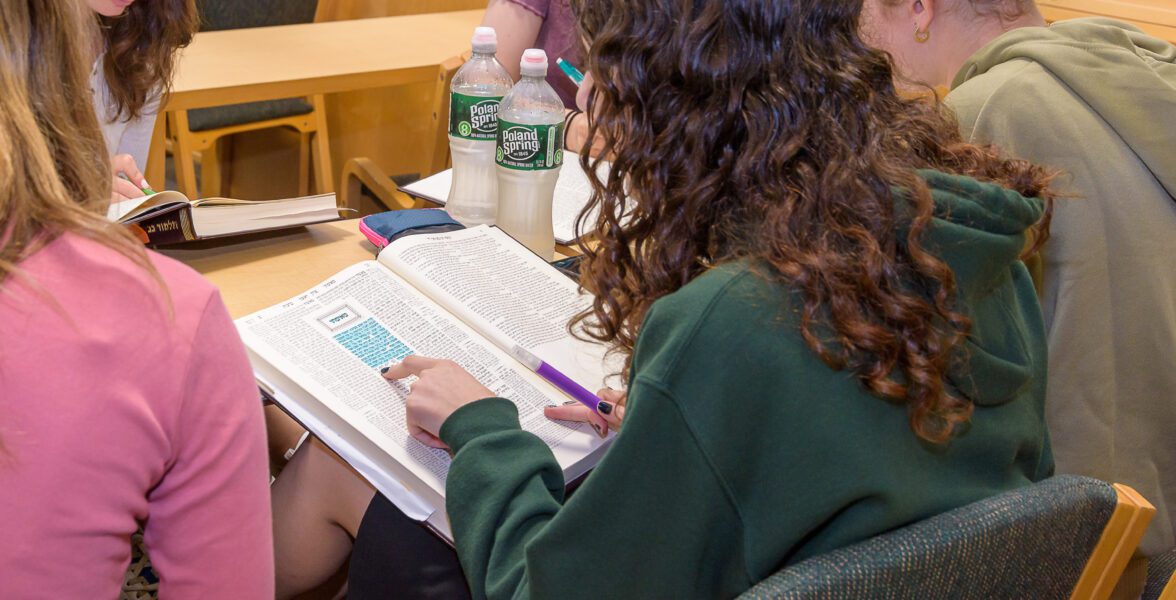

My high school students are often puzzled by drashot . Why does the Gemara use this particular pasuk to ground its halakha? Is that what the pasuk actually means? If not, what are Chazal trying to do? When the Gemara offers multiple suggestions of prooftexts with debate around each one, my students perceive the discussion as a type of game, but they are unsure of what the rules were, or if rules even existed. As a teacher, drashot often provide the opportunity to uncover, along with my students, the agenda of a sugya and the larger ideological concerns of Chazal. Methodologically, this entails tracing the antecedents of a drasha in the Gemara to the original pshat of the pasuk, tracing the pasuk through midreshei halakha and comparing how the drasha is used in the sugya at hand to other sugyot. When we observe shifts over multiple sources, we begin to appreciate that the Gemara made deliberate choices to advance a particular agenda. That agenda often has religious valence, highlighting the relative importance of a particular mitzvah or modeling how ancient values can be balanced with new realities. Such valence is the reason to do the work of uncovering. This paper, in an attempt to uncover the message chazal want to convey, looks closely at the drashot in Sanhedrin 73a surrounding the obligation to intervene to save a life.

The Sugya

גופא מניין לרואה את חברו שהוא טובע בנהר או חיה גוררתו או לסטין באין עליו שהוא חייב להצילו ת”ל לא תעמוד על דם רעך והא מהכא נפקא מהתם נפקא אבדת גופו מניין ת”ל והשבותו לו אי מהתם הוה אמינא ה”מ בנפשיה אבל מיטרח ומיגר אגורי אימא לא קמ”ל

Concerning the matter itself, it is taught in a baraita: From where is it derived that one who sees another drowning in a river, or being dragged away by a wild animal, or being attacked by bandits, is obligated to save him? The verse states: “You shall not stand idly by the blood of another” (Leviticus 19:16). The Gemara asks about this derivation: But is this really derived from here? It is derived from there, i.e., from a different verse, as it is taught: The Torah teaches that one must return lost property to its rightful owner. But from where is it derived that one must help his neighbor who may suffer the loss of his body or his health? The verse states: “And you shall restore it [vahashevato] to him [lo]” (Deuteronomy 22:2), which can also be read as: And you shall restore him [vehashevato] to him, i.e., saving his body. Consequently, there should be no need for the additional verse: “You shall not stand idly by the blood of another.” The Gemara answers: If this halakha were derived only from there, I would say that this matter applies only to saving the person in danger by himself, i.e., that he himself must come to his neighbor’s rescue if he can, as is the halakha with regard to returning a lost item. But to trouble himself and hire workers for this purpose, one might say that he is not obligated, just as he is not obligated to hire workers to recover another’s lost item. Therefore, the verse “Do not stand by the blood of another” teaches us that he must even hire workers, and he transgresses a prohibition if he does not do so.

In this short sugya, the Gemara picks up on a discussion earlier the daf that suggested the pasuk of לא תעמוד על דם רעך as proof for the halakha of rodef – that someone about to kill someone else should be killed prior to committing the crime. לא תעמוד is rejected as proof because it is instead needed to prove that an individual cannot stand idly by when a life is in danger. The sugya will not allow the pasuk to serve as a source for two drashot. The Gemara then says גופא – let us return to examine in further depth a topic raised earlier. After restating this drasha, the Gemara asks if the halakha of intervening to save a life should instead be learned from a pasuk in Vayikra dealing with returning lost objects. The Gemara rejects the suggestion in favor of לא תעמוד because לא תעמוד is more expansive in its demands on the bystander: it requires the bystander hire someone else to save the person at risk if she is not able to do so herself whereas the pasuk in the context of השבת אבידה would limit responsibility to only what the bystander is able to do alone.

My students and I are always puzzled by the suggestion of an alternate prooftext here. At this point the Gemara has established לא תעמוד as the source for intervening to save a life. Why offer an alternate suggestion at all? And why offer it from the context of השבת אבידה which deals with lost objects and not loss of life? The conclusion of the Gemara provides a partial answer to this question; in contrasting the two proofs the Gemara is able to show how far a bystander must go to intervene. But we are left bothered by how the drasha of והשבותו לו actually works and why the Gemara offered a suggestion to then reject it. A close look at the pesukim of לא תעמוד and והשבותו לו as well as their respective histories in midreshei halakha helps answer these questions and amplifies the ideological message of our sugya.

לא תעמוד – The Pesukim

The Tannaitic source quoted in the Bavli assumes that לא תעמוד על דם רעך means “do not stand idle when your friend is in danger.” While this is certainly a reasonable read of the pasuk, there are other possible interpretations.

Vayikra 19, 15-16

לֹא־תַעֲשׂ֥וּ עָ֙וֶל֙ בַּמִּשְׁפָּ֔ט לֹא־תִשָּׂ֣א פְנֵי־דָ֔ל וְלֹ֥א תֶהְדַּ֖ר פְּנֵ֣י גָד֑וֹל בְּצֶ֖דֶק תִּשְׁפֹּ֥ט עֲמִיתֶֽךָ׃

לֹא־תֵלֵ֤ךְ רָכִיל֙ בְּעַמֶּ֔יךָ לֹ֥א תַעֲמֹ֖ד עַל־דַּ֣ם רֵעֶ֑ךָ אֲנִ֖י יְהֹוָֽה׃You shall not render an unfair decision: do not favor the poor or show deference to the rich; judge your kin fairly.

Do not deal basely with members of your people. Do not profit by the blood of your fellow [Israelite]: I am יהוה.

The pasuk is found in Parshat Kedoshim in the context of a series of “holiness laws,” most of which govern interpersonal interaction. While the halakhot jump from topic to topic, the larger message of the section is that interpersonal ethics and creating a just society bring about kedusha.

One alternative read of the pasuk is “do not rise against your friend to kill him,” that is, this pasuk is a prohibition against murder. This interpretation is favored by Onkelos, Ibn Ezra, and Ramban, all close readers of pshat. Ibn Ezra connects the two parts of the pasuk: do not spread rumors about your friend, as that will result in his death. A second, similar possibility connects the two parts of our pasuk but also views them in light of the court context presented in the preceding pasuk. Slander may lead to a conviction in court, which leads to death; hence, “do not spread rumors that will lead to your friend’s death by the hands of the court.” The absence of a vav between the two halakhot in our pasuk, while present in so many pesukim in this parsha may indicate that we are to read לֹא־תֵלֵ֤ךְ רָכִיל֙ and לֹ֥א תַעֲמֹ֖ד as connected. A third possibility for understanding the pasuk is “do not profit by the blood of your friend.” In this case the words עמד על indicate “surviving by.”

As a learner of Chazal I hear the phrase לא תעמוד and automatically assimilate it as a prohibition of standing by when life is in danger. Pausing to understand there are alternative ways to read this pasuk, some of which make more contextual sense, helps me appreciate that the baal hasugya is making an interpretive act in putting forth their halakha of intervention. Put simply לא תעמוד doesn’t have to mean don’t stand idly by; this halakha didn’t have to exist in the first place – it exists because of an act of interpretation. This point is amplified by a look at the midreshei halakha.

לא תעמוד – Midreshei Halakha

Drashot on לא תעמוד are found in two works of Midrash Halakha. Vayikra Rabbah 24 reads:

תָּנֵי רַבִּי חִיָּא פָּרָשָׁה זוֹ נֶאֶמְרָה בְּהַקְהֵל מִפְּנֵי שֶׁרֹב גּוּפֵי תוֹרָה תְּלוּיִן בָּהּ רַבִּי לֵוִי אָמַר מִפְּנֵי שֶׁעֲשֶׂרֶת הַדִּבְּרוֹת כְּלוּלִין בְּתוֹכָהּ (שמות כ ב): אָנֹכִי ה’ אֱלֹהֶיךָ וּכְתִיב הָכָא (ויקרא יט ב): אֲנִי ה’ אֱלֹהֵיכֶם. (שמות כ ג): לֹא יִהְיֶה לְךָ וּכְתִיב הָכָא (ויקרא יט ד): וֵאלֹהֵי מַסֵּכָה לֹא תַעֲשׂוּ לָכֶם. (שמות כ ז): לֹא תִשָּׂא וּכְתִיב הָכָא (ויקרא יט יב): וְלֹא תִשָּׁבְעוּ בִשְׁמִי. (שמות כ ח): זָכוֹר אֶת יוֹם הַשַּׁבָּת וּכְתִיב הָכָא (ויקרא יט ג): אֶת שַׁבְּתֹתַי תִּשְׁמֹרוּ. (שמות כ יב): כַּבֵּד אֶת אָבִיךָ וְאֶת אִמֶּךָ וּכְתִיב הָכָא (ויקרא יט ג): אִישׁ אִמּוֹ וְאָבִיו תִּירָאוּ. (שמות כ יג): לֹא תִּרְצָח וּכְתִיב הָכָא (ויקרא יט טז): לֹא תַעֲמֹד עַל דַּם רֵעֶךָ. (שמות כ יג): לֹא תִּנְאָף וּכְתִיב הָכָא (ויקרא כ י): מוֹת יוּמַת הַנֹּאֵף וְהַנֹּאָפֶת. (שמות כ יג): לֹא תִּגְנֹב וּכְתִיב הָכָא (ויקרא יט יא): לֹא תִּגְנֹבוּ. (שמות כ יג): לֹא תַעֲנֶה וּכְתִיב הָכָא (ויקרא יט טז): לֹא תֵלֵךְ רָכִיל. (שמות כ יג): לֹא תַחְמֹד וּכְתִיב הָכָא (ויקרא יט יח): וְאָהַבְתָּ לְרֵעֲךָ כָּמוֹךָ

Rabbi Ḥiyya taught: This portion was stated in an assembly because most of the essential principles of the Torah are dependent upon it. Rabbi Levi said: Because the Ten Commandments are included in it. “I am the Lord your God” (Exodus 20:2), and it is written here: “I am the Lord your God” (Leviticus 19:2). “You shall have no [other gods before Me]” (Exodus 20:3), and it is written here: “Do not make molten gods for yourselves” (Leviticus 19:4). “You shall not take [the name of the Lord your God in vain]” (Exodus 20:7), and it is written here: “You shall not take an oath in My name falsely” (Leviticus 19:8). “Remember the Sabbath day to sanctify it” (Exodus 20:8), and it is written here: “And you shall observe My Sabbaths” (Leviticus 19:3). “Honor your father and your mother” (Exodus 20:12), and it is written here: “Each of you shall revere his mother and father” (Leviticus 19:3). “You shall not murder” (Exodus 20:13), and it is written here: “You shall not stand by the blood of your neighbor” (Leviticus 19:16). “You shall not commit adultery” (Exodus 20:13), and it is written here: “The adulterer and the adulteress shall be put to death” (Leviticus 20:10). “You shall not steal” (Exodus 20:13), and it is written here: “You shall not steal” (Leviticus 19:11). “You shall not bear [false witness]” (Exodus 20:13), and it is written here: “You shall not go as a gossip” (Leviticus 19:16). “You shall not covet” (Exodus 20:14), and it is written here: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18).

This midrash makes order of the seemingly random halakhot presented in Vayikra 19 by connecting them to the aseret hadibrot. In this context לא תעמוד is most simply understood as an injunction against murder parallel to לֹא תִּרְצָח. The existence of this midrash again helps us appreciate the interpretive act of our Gemara in understanding לא תעמוד as a halakha of intervention: it can simply be read as “don’t murder.”

The source of the drasha in our Gemara is Sifra Kedoshim 4, 6-7.

[ו] אמר רבי נחמיה כך הוא מנהגם של דיינים: בעלי דין עומדים לפניהם ושומעים את דבריהם ומוציאים אותם לחוץ ונושאים ונותנים בדבר. גמרו את הדבר הזה מכניסים אותם הגדול שבדיינים אומר “איש פלוני אתה זכאי איש פלוני אתה חייב”.

[ז] ומנין שכשיצא אחד מן הדיינים לא יאמר “אני מזכה וחבירי מחייבים אבל מה אעשה ורבו עלי” לכך נאמר “לא תלך רכיל בעמך”. וכן הוא אומר “הולך רכיל מגלה סוד ונאמן רוח מכסה דבר” (משלי יא יג)

[ח] ומנין שאם אתה יודע לו עדות שאין אתה רשאי לשתוק עליו? תלמוד לומר “לא תעמוד על דם רעך”. ומנין אם

ראית טובע בנהר או לסטים באים עליו או חיה רעה באה עליו חייב אתה להצילו בנפשו? תלמוד לומר “לא תעמוד על דם רעך”. ומנין לרודף אחר חבירו להורגו ואחר הזכור ואחר נערה המאורסה חייב אתה להצילו בנפשו? תלמוד לומר “לא תעמוד על דם רעך”.And whence is it derived that if one of the judges goes out, he should not say “I found for you, but what can I do, my fellow (judges) are in the majority”? From “You shall not go rachil among your people.” And (Mishlei 11:13) “He who goes rachil reveals a secret, and the faithful of spirit conceals a thing.”

And whence is it derived that if you can testify on someone’s behalf, you are not permitted to remain silent? From “You shall not stand by the blood of your neighbor.” And whence is it derived that if you see someone drowning in the river or being waylaid by robbers or attacked by a wild beast, that you must rescue him? From “You shall not stand by the blood of your neighbor.” And whence is it derived that (if you see) a man pursuing another to kill him or to sodomize him, or after a betrothed maiden, that you must rescue the pursued by (taking) the life of the pursuer? From “You shall not stand by the blood of your neighbor.” (Vayikra 19:17) “You shall not hate your brother in your heart. Reprove shall you reprove your neighbor, but do not bear sin because of him.”) “You shall not hate your brother”: I might think (that this means) that he should not curse him or strike him or slap him; it is, therefore, written “in your heart.” Scripture speaks only of hatred in the heart. And whence is it derived that if he reproved him four or five times (and he did not take heed), he should keep on doing so? From “Reprove shall you reprove.” I might think that he must do so even if his face changes color (in shame); it is, therefore, written “but do not bear sin because of him.”

This midrash reads לא תלך רכיל in the context of the preceding pesukim relating to judges. It extends that context to לא תעמוד presenting it as the source for a prohibition for withholding evidence. Using the same formula of מנין the midrash proceeds to present לא תעמוד as the source of two additional halakhot the requirement to intervene to save a life and the halakha of rodef. It is notable that our Gemara explicitly rejects the notion of learning multiple halakhot from לא תעמוד while the midrash has a list that includes two of the three halakhot mentioned in our Gemara in connection with לא תעמוד. This is in line with the Bavli’s general approach of using a pasuk to learn only one halakha. However the existence of multiple interpretations of לא תעמוד in this midrash underscores that our Gemara was preferencing one of them. It was important for our Gemara to preserve a halakha of intervention and hence that became the sole meaning of לא תעמוד.

When working through these midreshei halakha my students appreciate that our Gemara is not simply copying and pasting earlier sources but using earlier material to craft a message; in this case that I must intervene to save a life. However learning through the Sifra strengthens our earlier question about והשבותו לו. If our Gemara is based on a midrash that explicitly asks and then answers the question of how we know I must intervene why turn at all to another context for the answer? And why specifically השבת אבידה?

השבת אבידה – The Pesukim

דברים כב א-ג

לֹא תִרְאֶה אֶת שׁוֹר אָחִיךָ אוֹ אֶת שֵׂיוֹ נִדָּחִים וְהִתְעַלַּמְתָּ מֵהֶם הָשֵׁב תְּשִׁיבֵם לְאָחִיךָ:

וְאִם לֹא קָרוֹב אָחִיךָ אֵלֶיךָ וְלֹא יְדַעְתּוֹ וַאֲסַפְתּוֹ אֶל תּוֹךְ בֵּיתֶךָ וְהָיָה עִמְּךָ עַד דְּרֹשׁ אָחִיךָ אֹתוֹ וַהֲשֵׁבֹתוֹ לוֹ/:

וְכֵן תַּעֲשֶׂה לַחֲמֹרוֹ וְכֵן תַּעֲשֶׂה לְשִׂמְלָתוֹ וְכֵן תַּעֲשֶׂה לְכָל אֲבֵדַת אָחִיךָ אֲשֶׁר תֹּאבַד מִמֶּנּוּ וּמְצָאתָהּ לֹא תוּכַל לְהִתְעַלֵּם:If you see your fellow Israelite’s ox or sheep gone astray, do not ignore it; you must take it back to your peer.

If your fellow Israelite does not live near you or you do not know who [the owner] is, you shall bring it home and it shall remain with you until your peer claims it; then you shall give it back.

You shall do the same with that person’s ass; you shall do the same with that person’s garment; and so too shall you do with anything that your fellow Israelite loses and you find: you must not remain indifferent.

As is the case with לא תעמוד the pesukim about hashavat aveida appear in a broader context of halakhot relating to creating a just society. I like to tell my students that hashavat aveida is my favorite mitzvah because the idea is incredibly radical. The Torah does not say it is a good deed for me to return your lost object; it says I have done something wrong if I do not! Writ large the Torah is creating a society in which we are all responsible for each other’s property which is generally not how we think about personal possessions. The Torah is aware of the counterintuitive nature of this halakha and hence stresses – twice – the idea that I cannot do what it is human nature to do: simply walk by and pretend I did not see the lost object לֹא תוּכַל לְהִתְעַלֵּם.

In the context of these pesukim the words והשבותו לו mean “return it to him,” clearly meaning return the lost object to its original owner. In the drasha proposed in our Gemara, the words are shifted to mean “return his life to him,” that is, if his life is in danger, do not stand idly by. If the pesukim are not at all talking about loss of life, how do we understand this drasha? Rashi on our Gemara suggests:

ת”ל והשבותו לו – קרא יתירא הוא למדרש השב את גופו לעצמו:

The pasuk says “Return it to him.” The extra phrase indicates return his body to him.

The claim is that once the command to return the lost object has been stated in the opening pasuk, it is repetitive to again state that the object must be returned. While this functions on the level of a drasha, the two pesukim are not actually repetitive; one is a general injunction to return a lost object, and the second is instruction as to how to handle the lost object when I do not know the owner. Understanding that Chazal were sensitive to repetition, it is still quite a jump from the context of returning lost objects – ie, “return the lost object to its owner,” to the context of saving a life – “return his life to him.” How and why did our Gemara make this jump?

והשבותו לו -Midrash Halakha

The origin of the והשבותו לו drasha in our Gemara is found in Sifre Devarim 223 4:

והשבותו לו. ראה היאך תשיבנו לו שלא יאכיל עגל לעגלים סייח לסייחים. וכל דבר שעושה ואוכל כגון חמור ופרה עושה ואוכלת. והשבותו לו. אף את עצמו אתה משיב.

“and you shall return it to him”: Consider how to return it to him. He may not feed “a calf to a calf, a foal to a foal” (i.e., he may not sell one of the animals in his keeping to feed the others.) And any animal which can work and eat (i.e., an animal whose work is worth the cost of its food), such as an ass or a cow, let it work and eat. “and you shall return it (also readable as “him”) to him”: He himself must be returned to him (if he is lost).

In the two drashot on והשבותו לו presented here the first interprets והשבותו לו as referring to the lost object whereas the second extends the obligation of returning lost objects to returning lost persons. That is והשבותו לו can mean “return it (the object) to him,” or it can mean “return him (the person) to himself. Unlike our Gemara the midrash read in context is not talking about a life in danger; it is talking about helping a lost person find his way.

A version of this midrash is found in Bava Kamma 81b. The Gemara states that one who is lost is able to cut down branches on someone else’s property in order to find his way. It continues:

הָא דְּאוֹרָיְיתָא הוּא דְּתַנְיָא הֲשָׁבַת גּוּפוֹ מִנַּיִין תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר וַהֲשֵׁבוֹתוֹ דְּאוֹרָיְיתָא הוּא דְּקָאֵי בֵּי מִיצְרֵי אֲתָא הוּא תַּקֵּין דִּמְפַסֵּיג וְעוֹלֶה מְפַסֵּיג וְיוֹרֵד:

The verse states: “And you shall restore it to him” (Deuteronomy 22:2), which can also be translated as: And you shall restore himself to him.

If this is required by Torah law, why did Joshua stipulate a condition to this effect? The Gemara answers: By Torah law one is required only to walk in a roundabout path along the boundaries, without damaging another’s vines by cutting off branches. Joshua came and instituted the stipulation that one may go even further and cut off branches and ascend or cut off branches and descend, thereby leaving through the most direct route.

The Gemara asks why there is a need for a special stipulation regarding cutting of trees. It then quotes a Tannaitic source (seemingly based on Sifre): “how do we know there is an obligation to return a lost body?” The answer of course is והשבותו לו. Here it is quite explicit that the context is about a person who is lost. The Gemara in Bava Kamma adopts the interpretation of והשבותו לו presented in the Sifre; והשבותו לו extends the commandment to return lost objects to helping people who are lost find their way. Neither the Sifre nor Bava Kamma mentions anything about saving a life in the context of והשבותו לו.

Returning to Our Sugya

Having looked at the pesukim and midreshei halakha we are in a better position to understand the interpretive moves our sugya is making. First there was a move to understand לא תעמוד as a prohibition against standing by when life is in danger and to preference that interpretation over others. Second our sugya expands the parameters of this obligation as much as possible by setting up the drasha of והשבותו לו as a foil to לא תעמוד. While this is evident to some degree in an initial read of the sugya, it is made much clearer by our look at the midrash halakha.

Our sugya subverts the meaning of the original drasha on והשבותו לו which deals with the need to help someone find their way and turns it into a drasha regarding not being a bystander when life is at stake. It uses similar phraseology but adapts it to a totally different context, giving the drasha an entirely different meaning! The subtle shift in language between the question of הֲשָׁבַת גּוּפוֹ מִנַּיִין as found in Bava Kamma and אבדת גופו מניין as found in our sugya is a mechanism that helps push this interpretive shift; אבדת גופו sounds more clearly like loss of life. Seeing that our sugya takes a drasha totally out of context and shifts its meaning in order for the drasha to be rejected helps us appreciate the degree to which השבת אבידה is a foil for pushing a more expansive understanding of a halakha of intervention.

To return to our original question why does the Gemara turn to השבת אבידה in its quest to expand the parameters of לא תעמוד? The question is amplified by the fact that the drashot on השבת אבידה do not at all deal with loss of life. As is the Torah Chazal were sensitive to human nature. As mentioned earlier with regard to lost objects the Torah goes out of its way to say (twice!) לֹא תוּכַל לְהִתְעַלֵּם. Our impulse may be to walk by but that is not how a just society functions. I am responsible for the objects of another person. The same impulse to walk by is present when I see a person in danger; I may want to walk by and pretend I didn’t see it. The impulse to ignore may be even stronger in the case of a person as the effort required of me is likely greater. Halakha is unique in having a “Good Samaritan Law,” not simply a law that punishes the “Bad Samaritan.” On the level of human impulse השבת אבידה is a natural place for Chazal to test the limits of how far I need to go to save a life. Our Gemara then rejects the connection it created making the point that despite the fact that I have a counterintuitive obligation towards someone else’s property I have a much stronger obligation towards someone else’s life. לא תעמוד obligates me not only to intervene but to use my own resources to intervene with the costs unspecified.

A Word on Accessibility

With a higher-level class, I might choose to learn all of the midrashim inside over the course of a few class periods. With a foundational class, I might choose to only look back at the pesukim for one period. Either way, this kind of work – tracing this sugya back so we understand the values of Chazal on the daf at hand – can be done with a wide range of students. Whether or not I choose to learn through every midrash halakha with every class, this type of work is certainly important for me as a teacher in terms of highlighting the message I should focus on when teaching this sugya.

In Conclusion:

Doing the work required to identify the value animating a sugya enables my students and I to take the next steps in a more informed, nuanced way. Now that we understand the lengths to which our sugya went to expand bystander responsibility, we can ask a different set of questions: How exactly should the economics be handled? How much danger, if at all, should I put myself in to save a life? In a hyper-connected world, do I have a responsibility to save a life that is virtually, but not physically, in front of me? An understanding of the development of our sugya helps us approach these new questions grounded in the values of Chazal.