Educating Toward Spirituality

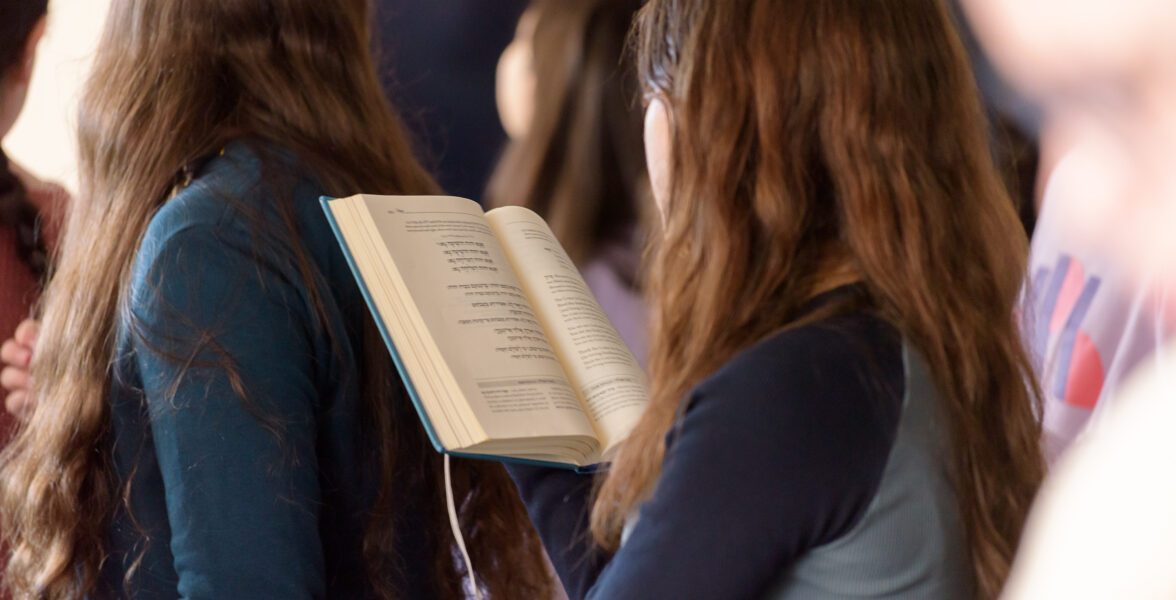

As a shacharit teacher entering the davening space on any particular morning, I have a long wish-list of what I want for my students. I want them to understand the words they recite. I want them to connect with the community of mitpallelim present in the room. I want them to see themselves as part of a community of mitpallelim stretching throughout Jewish history. I want them to feel comfortable in a shul environment. I want them to experience a sense of awe in standing before Hashem. As a mitpallelet, at the same moment I also want all of those things for myself. When we pause to iterate our goals as tefillah educators, we have such an overwhelming number of goals that it is impossible to focus on, let alone make headway towards, any single one. All of these goals are important (and any group of day school shacharit teachers will add to the list); we are just trying to achieve too many of them at once.1 This paper is an argument for homing in on ONE particular goal in our educational tefillah spaces — and constructing those spaces to achieve that goal. My focus here is on high school, as that is the environment I inhabit, but has implications for how we might construct tefillah education in middle and elementary school.

Educating Towards Shul vs. Educating Towards Spirituality

In the current Modern Orthodox high school environment, we, whether by conscious decision or force of adult habit, are educating towards shul. Tefillah in school tends to mimic our adult shul environment. We expect our students to show up, to take a siddur, to know when to stand or sit, to know when it is appropriate to talk and when it is not, to listen to the rabbi, to volunteer for the community. We are socializing our children so they will feel comfortable in a shul environment, so that they will know how to “do shul.” This entails familiarity with a specialized language and an intricate choreography. When done well, educating towards shul entails explicitly communicating the value of ritualized community to our students and helping them draw a line between discrete actions and a larger goal. When done less well, we simply mimic shul rather than educate towards it.

Ensuring that our students are comfortable in shul is a crucial goal. And yet, in the interest of pinpointing a single goal, we need to turn our attention away from educating towards shul to educating towards spirituality. Spirituality is a notoriously fuzzy word: it can mean connecting with oneself, a meditative state, or awareness of the wonder beyond. I use it here in an explicitly Jewish religious context. Our educational tefillah space should help students foster a sense of deep connection with God. It should be a space where students have the opportunity to pause from their routines, appreciate the expansiveness of the world around them, feel gratitude, and allow God to enter their lives. The goal is for this sense of connection to spill over into other areas of life: how they say brachot, how they appreciate the natural world around them. Such spillage will only occur if there is a focus on individual personal connection, not only on communal norms. When we educate towards shul we are focused on the practical goal of enabling students to participate in adult community. When we educate towards spirituality, we are focused on helping students develop a sense of connection. Shul is a means towards a goal but not the goal itself.

It can be argued that educating towards shul is crucial to developing a longstanding community of practice and that shifting to focus on individual connection will ultimately be detrimental to the continuity of the community. It is important here to differentiate between adults and children. Adults who attend shul are choosing to be there. Many reasons might undergird this choice — a sense of chiyyuv, a desire to carry on tradition, a desire to fit in with a community, a personal spiritual sense. For most, it is likely a complex mix of all of the above, with the predominant reason shifting over time. Some adult shul goers don’t pick up a siddur, and others say every word of davening but don’t experience spirituality in shul. But our day school children, regardless of whether they want to be there – are required to attend shacharit in school. They are not making a personal choice to opt in. How can we best use the time we have with them to ensure that tefillah is a personally meaningful experience that will encourage them to lead religiously meaningful lives?

We cannot make progress towards this goal by convincing them to daven out of chiyyuv, or because Jews have always davened, or out of fealty to the community. If a sense of personal connection is lacking, none of these ideas carry valence on their own. Some teens are very good rule followers and will do what is expected of them in shacharit, and those teens may grow into adults who show up in shul out of a sense of communal obligation — they are still following the rules. But those teens turned adults might not experience real encounter. The communal aspect of tefillah is crucial, as is the notion of fulfilling a chiyyuv. But students are likely to come to appreciate the value of community on their own, without its being our primary focus. And, in our Modern Orthodox community, valuing chiyyuv stems from an internalized connection.

I am not arguing that chazal originally intended davening to be about personal connection as opposed to chiyyuv. Prooftexts can be marshalled in either direction. Nor should we expect that tefillah be meaningful at every single moment. Our expectations must be realistic; our goals achievable. I am arguing that, at this time, for the Modern Orthodox day school student, we have an imperative to address our students’ spiritual lives.

If the goal of helping students develop inner spiritual lives is important, why not find other time in school when we can teach towards this goal? Why not educate towards shul during tefillah and spend time outside of the tefillah space talking with students about God and helping students locate meaning within tefillah? We absolutely need to utilize time outside of the tefillah environment to help students develop richer spiritual lives. But we need to shift how we use the time allocated for tefillah for two reasons. The first is practical. We are pressed for time in our schools, and tefillah provides us with a block of time that is already set aside for connecting to God. When I look around during shacharit, many students are engaged for selected parts of tefillah, but there is also a great deal of “wasted time:” parts of davening during which students are predominately passive and not engaged in any sort of meaningful experience. Calculated daily, over a four year span of high school, this time adds up. We need to consider how to use this time so that students are actively engaged in spiritual development. Secondly, and more significantly, if the goal is to help students develop a deep sense of connection, the tefillah space must be the locus. If we want students to develop meaningful davening lives – to not just go to shul but to actually DAVEN, we need to focus on shifting our educational davening spaces. We want our students to not just theorize and talk about davening and connection in a classroom setting but to actually DO and practice and experiment in the most common space where it will occur during their adult lives — a tefillah space.

I am wary of over-problematizing or of declaring a “davening crisis.” When I look around at shacharit on any typical day, many students are fully engaged in tefillah. However, I am most struck by the students who are sometimes or somewhat engaged. This often takes the form of disengagement until shmoneh esreh, at which point they daven a long and seemingly focused amidah, many of them shuckling away. There are also students who will daven beautifully one day and not at all the next. This intermittent davening suggests that students are looking to connect, and we need to provide the right push, set the proper stage. Given an innate desire, I am hopeful about what our students’ spiritual lives might be.

Less is More

Our tefillah spaces need to look like tefillah and feel like tefillah. Put simply, if we want students to connect to God through davening, there has to be davening. This means that tefillah time should consist primarily of tefillah, and while experiences like art, meditation, or journaling may help a student connect, those experiences should all be in the service of tefillah. How the time is divided is crucial. There is a distinction, for example, between a minyan that calls itself meditation with tefillah, or a minyan that calls itself tefillah with meditation.2 Students are always the best reporters of where our priorities lie; when a student leaves minyan and I ask her if she meditated or if she davened, what will she answer?

That said, our schools need to be much more radical than we currently are about omitting parts of tefillah for almost all of our students in order to allow more time to properly shape and frame the tefillah experience. Our students will be better off by having a shorter, more meaningful tefillah than by having a longer, drawn out one. We do not need to rush to say everything, and we need to use the time we have to encourage maximal engagement. Very practically, I advocate for a bare-bones halakhic davening. That means saying birkhot hashachar, baruch she-amar, ashrei, yistabach, and birkhot kriyat shema through shmoneh esreh. On Mondays and Thursdays we should layn. We should do a heicha kedusha on all days.3

An Example of Educating Towards Spirituality: Pticha

We need to create experiences that help students appreciate being in the tefillah space, so that they can carry that experience with them and draw strength from it. I propose spending the first ten minutes of the time allotted for shacharit each morning engaged in a Pticha- an opening activity that helps set the tone for tefillah. In this way, we cordon off davening itself so that it is not interrupted by explanations or meditation. Tefillah is tefillah. We take time, however, prior to tefillah to focus on the importance of the endeavor upon which we are about to embark. Preparing to enter the tefillah space is an ancient idea advocated by chazal (Mishna Brachot 5,1)

חֲסִידִים הָרִאשׁוֹנִים הָיוּ שׁוֹהִים שָׁעָה אַחַת וּמִתְפַּלְּלִים, כְּדֵי שֶׁיְּכַוְּנוּ אֶת לִבָּם לַמָּקוֹםThe early generations of pious men would wait one hour, in order to reach the solemn frame of mind appropriate for prayer, and then pray, so that they would focus their hearts toward their Father in Heaven.

The time has come to give this idea new life within our educational settings.

How can we set the proper tone? If the goal is to encourage spiritual growth, we need to provide students with multiple paths of connection. We should offer a number of different minyanim, each with a different Pticha experience to appeal to a range of students or to students searching for distinct experiences at varied stages of their development. For high school students, the very notion of being offered choice, and that the choice one makes is respected, can be even more significant than the actual content of the choice. As adults, we can choose to go to the very quick hashkama minyan, the Carlebach minyan, the minyan where the rabbi speaks or the minyan where the rabbi doesn’t speak.4 When we offer students similar choices, we respect them as young adults able to make thoughtful decisions about their davening lives. It is important that students attend the same minyan consistently so they can develop a connection to that space and relationships with adults and peers but also that they are granted flexibility when changes need to be made.

Tachlis, what might happen from 8:00-8:10 on a Monday morning? Below are some options of what various Ptichot might look like. Many of these ideas have antecedents in halakha or Jewish History.

Song: Students begin their day with a niggun, and the first ten minutes of shacharit time are spent in song. Students who are so inclined can bring instruments. Students can participate through leading and choosing the songs. The songs can vary with the Jewish calendar or respond to a particular moment in the school or current events.

Chabura: The power of the tzibbur can be leveraged to help students connect to the experience they are about to enter. Shacharit can begin with small group check-ins and daily routines where each student has to share something he or she brings to the experience that morning. What are you davening for today? What is something you want to leave behind as you start tefillah? What is going on for you today? On a scale of 1-10, how are you feeling today and why? Asking the same question each day will help create a powerful sense of routine, and peppering this routine with new questions will keep it fresh.

Meditation: Shacharit can begin with ten minutes of meditation. The meditation can be focused on a particular area of tefillah so that it is connected to the tefillah experience and leads directly into it.

Journaling: Students can start their day with journaling. Students can write about their state of mind, what they are bringing to tefillah, whether or not they feel connected and why, and who and what they are davening for. Journaling can set the tone for entering tefillah in a reflective mindset.

Vaad Mussar / Tikkun Hamiddot: Shacharit can begin with a focus on character development, with different middot presented as discrete units. The teacher might teach some Torah related to a particular middah – for example, anava, and lead a discussion around that middah. Students can be asked to share their experiences and struggles with that middah. They can be given “assignments” so that they practice exercising that middah, and then report back on triumphs and challenges. This can be done either with the group or with a chavruta. The goal is to enter davening space in a reflective space focused on personal growth.

These Pticha options do not need to be so distinct – one might want to combine elements of a few of these with any particular group of students. Instead of rushing into the tefillah space, we enter and approach it slowly so that our focus is now on tefillah. For each of these options, it is important to have a set routine so students know what to expect each day and understand this expectation as moving towards a goal. This means singing the same song, asking the same question, responding to the same journal prompt. But it is also important to add new songs, new questions and new prompts to the standard routine so that there is a sense of chiddush.

Most significantly, whatever our Pticha might be, it is important that students actively engage. There must be a stated assumption that for each of these activities everyone has to DO something. That means singing, or sharing, or journaling, or responding to a peer. Sitting passively is not an option. When we allow choice, it makes requiring full engagement easier. When students are asked to DO something as opposed to just absorb something, when they have to expend effort, we increase the chances that the experience will spill over into davening and the rest of the day. Asking students to do something also ensures that, as we prepare for the Pticha, that we are student- rather than teacher-centered. In our preparation, we need to ask ourselves what we are asking the students to DO, not what am I, as a teacher, saying?

Structures to Support Effective Pticha

In order for the Pticha to be effective, we need to properly construe the physical space. When we run a shabbaton, we actively think about how the room can be set up to maximize participation for a tisch. We need to bring the same focus to our tefillah spaces each day and not just show up to daven in a room set up for something else. What are we asking students to DO, and how can the room best be set up to support that? How close or far apart do we want the students to be? Will they need to speak with each other, or do we want everyone in their own contemplative space? Where do we want to situate ourselves? How can we set up the space so that everyone is maximally involved? We may want to consider using outdoor space for the Pticha or even for shacharit. The key is thinking proactively about how the space can support our goals. We don’t just show up.

To execute a program of pticha effectively with students, it is crucial that teachers are first mitpallelim and then teachers. How do I, as a teacher, enter the tefillah experience in a way that is meaningful to me? If I dedicate ten minutes each morning to prepare for tefillah, what might that look like? Focusing first on myself as a mitpallelet will help maintain the authenticity of my efforts and avoid the depersonalization that often occurs in a rush to apply an idea in a classroom. To that end, before introducing the idea of the pticha to students, I propose creating a faculty group that meets twice a month over the course of a semester dedicated to practicing various ptichot. (Since logistics can often make or break an idea; perhaps the group could meet before mincha and daven mincha together twice a month). For the majority of the meetings, this group would focus only on their own experience of the ptichot and subsequent tefillah and not on planning what to do with students. Focus on the teacher allows for a more immersive experience and more creativity in experimentation. Most significantly, it will help teachers understand and internalize the possibilities of the project in a way that will enable meaningful translation to students when the time comes.

Adding a pticha to tefillah is not simply a matter of carving out the time in which to do; it requires structural shifts in how tefillah is organized in our schools. We need to take minyan size into account. We can run a shul with one hundred students, but we can’t run an effective pticha that way. Currently, our schools rarely communicate with parents about their children’s progress in tefillah, progress should be noted with anecdotal write ups and parent teacher conferences. What we choose to officially communicate about is a signifier of our values.

Changing minyan size and adding responsibilities such as preparation, teacher meetings and parent communication requires a shift in how teachers are compensated for tefillah. In most of our day schools, tefillah is an add-on in teachers’ schedules. The model needs to shift so that teachers are compensated for tefillah as a class. We might also consider shifting our schedules so that tefillah takes place second period rather than first, allowing students time to ease into their day and be fully present for the experience. None of these changes are simple, and none of them can be done immediately on a broad scale, but as we shift from educating towards shul to educating towards spirituality, it is important to consider the structural changes necessary to

support spiritual tefillah education, even if said changes need to be made over time.5

Thus far, I have focused on the high school setting, as that is the environment with which I am most familiar. However, if we are to effectively educate towards spirituality in our tefillah spaces, we should ideally start at a young age. For example, if students are exposed in preschool to the idea of a pticha — to needing to enter the tefillah space with a certain mindset — that will become a natural part of their tefillah experience. As they mature, the type of pticha will change, but they will be familiar with the concept of reflecting before tefillah. Students who learn at a young age — and continue to learn throughout older elementary and middle school years — that it is natural and appropriate to share thoughts about tefillah and about how they feel in God’s presence and to sing before and during tefillah — will be prepared and less cynical about doing so as they mature.

Concluding Thoughts

Much of the discussion of the challenges of tefillah in Modern Orthodox day schools is focused on students who have difficulty with tefillah and neglects to consider how we can challenge our “good” daveners to deepen their tefillah experience. Creating space for a pticha is an acknowledgement that all of us – even those of us who do not struggle with tefillah – can still work on what it means to enter this distinct space.

If we turn our attention from educating towards shul to educating towards spirituality, might we run the risk of devaluing the power of ritual, and particularly, of communal ritual? We need to be mindful not to educate a generation of students to daven by meditating alone in their backyards. We also need to help students understand the power of showing up each day, even if we aren’t “feeling it.” For these reasons, it is important that the work we do with students remains in the context of communal tefillah so that students should see that meaningful spiritual growth can occur within the context of a ritual praying community. The communal framework of tefillah helps us recognize that religious growth is not an individual endeavor; it allows us to strengthen each other and holds us accountable for showing up when we might not do so on our own. We need to design our educational tefillah experiences in such a way that leverages the power of the group. This can be done through singing with the group, reflecting on the communal language of our tefillah, sharing a journal entry, or discussing with a davening partner.

As we focus on helping students connect and not just on “doing shul,” we need to be explicit with students that our long term goal is providing them with tools to help them experience God in their lives. Tefillah is an important context for that encounter, but the goal of our work is to show students that the elongated ritual encounter of shacharit also occurs throughout the day in minituarized form. If I learn to pause and reflect before speaking to God, to pause to appreciate, to pause to make sure I am fully awake, I will more easily pause before putting food in my mouth or after going to the bathroom. As tefillah educators, we have the opportunity to show students the power of being present.

Footnotes

- Jamies Jacobson-Meisels makes this point in “A Vision of Tefillah Education,” Ha-Yidion: The Prizman Journal, Spring 2013 p. 18

- Formulation credited to Rabbi Tully Harcsztark

- I would make the same argument with regard to benching. I would rather students recite the first paragraph of bentching consistently, with kavana and a real sense of thankfulness for their food, than skip bentching altogether because it is too long. We need to consider what it means to educate towards this so that students understand that the first paragraph is a starting, and not an ending point.

- Formulation credited to Rabbi Tully Harcsztark

- Jay Goldmintz makes a powerful case for tefillah teachers thinking of their morning minyanim as classrooms. “On Becoming a Tefillah Educator,” Jewish Educational Leadership Vol 16:1 Fall 2017